Once, films that wanted to depict the LGBTQ+ community had to disguise their intentions – they were Queer Coding. We follow a series of movies which trace the evolution of queerdom from slyly suggestive to unabashedly representative.

Gay individuals were represented in Hollywood virtually from the beginning, be they as the butt of jokes or creepy villains. The 1930s Production Code expressly forbade any and all representations of what could in any way be interpreted as queer. This, of course, didn’t stop filmmakers from making sly references to queerdom. Alfred Hitchcock’s thrillers often alluded to gay characters (women in tweed suits, men in silk dressing gowns) for audience members with the eyes to see.

Nothing was ever explicit. Lesbians and gay men, starved of seeing themselves on the cinema screen couldn’t help but thrill when Doris Day in Calamity Jane (1953), dressed in fetching buckskins, sang of her ‘secret love’. According to Vito Russo’s book, “The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies,” gays in the audience howled with laughter when they saw a Queer Coded Joan Crawford dressed as a cowboy, in the camp Western Johnny Guitar (1954). By the late-1950s, however, films (particularly so in Europe) became ever more daring.

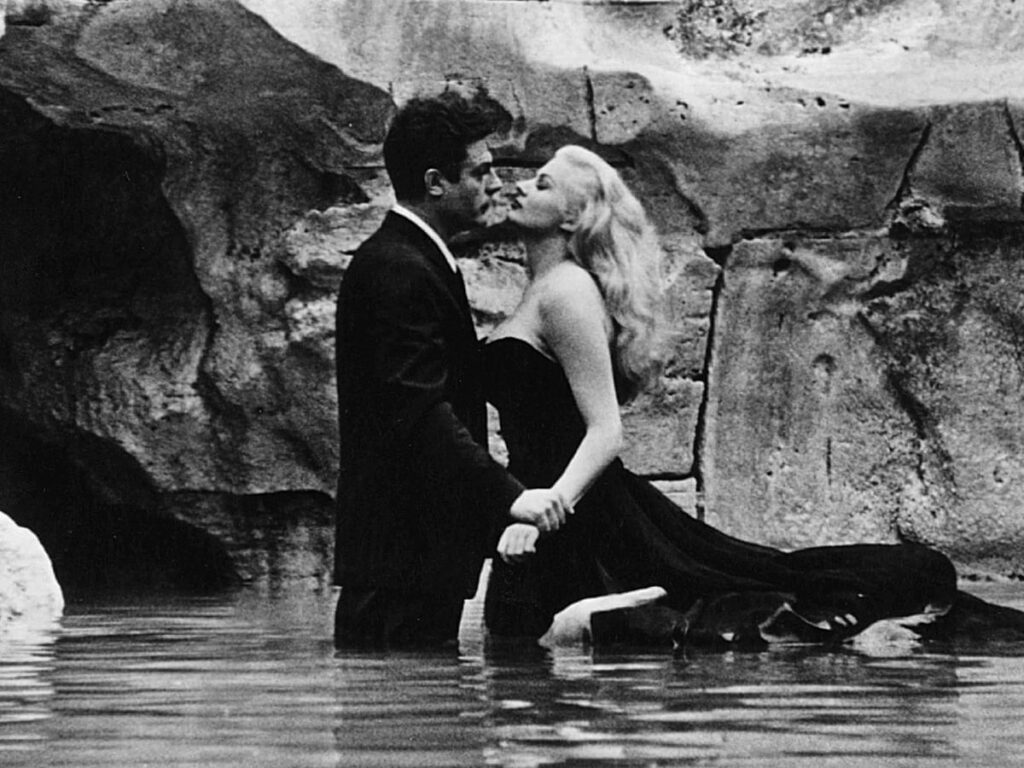

At the dawn of the new decade, Federico Fellini’s crossover art movie La Dolce Vita (1960) showed several unmistakeably gay characters (queer filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini was one of Fellini’s uncredited early collaborators on the film). Giò Stajano played a small recurring role as the gossip columnist hero’s informant and hanger-on. The actor was openly gay and in the 1980s became Italy’s best-known trans figure.

At one point near the end of the film, one gay reveller announces in a bleary, hungover drawl that, “By 1965 there’ll be total depravity. How squalid everything will be!” American gossip columnist Hedda Hopper was one of the film’s many denouncers in stating that it was full of “homosexuals, lesbians, a wealthy nymphomaniac… and repulsive orgies too sordid to write about”. No wonder there were queues around the block for the box office! La Dolce Vita was meant to be a denunciation of the empty bling of celebrity-obsessed western society, but made everything look so shockingly glamorous that audiences around the world lined up to see it.

Few filmmakers could be considered as daring as Janet Green and John Cormack, the writers of the pioneering Victim (1961), in which Dirk Bogarde played a closeted gay lawyer and a victim of blackmail (at a time when homosexuality was still illegal in the UK). In the US, change was slower. Hollywood was more comfortable with lesbianism – as in Walk on the Wild Side (1962) in which Barbara Stanwyck played a crazed brothel madam. In 1964, Sidney Lumet made The Pawnbroker in which the badass gangster played by Brock Peters is seen in his arty, all-white apartment and is clearly meant to be understood as gay. Yet blink, and you’re sure to miss it.

The youthquake of the 60s saw old conventions topple. There was a new openness about sexuality and permissiveness, as the counter culture flexed its muscles in demos, riots, its sexual liberation and general celebration of the dawning of the Age of Aquarius.

The big Hollywood studios were struggling, none more so than Twentieth-Century Fox, which was almost brought to its knees with the superflop Cleopatra (1963). In hopes of saving themselves from oblivion, studios looked to theatre, novels, and European films, which were giving hitherto taboo subjects a refreshing airing. Blow-Up (1966) titillated audiences with pot smoking and frontal nudity (and a snide reference to homosexuals). Fox Studio made the shocking Valley of the Dolls (1967) and Myra Breckinridge (1970), about an actress who travels to Hollywood after undergoing gender reassignment surgery. Both were based on bestselling novels and both were big money-spinners, but also truly trashy movies.

It also helped that the much-reviled Production Code was replaced in 1968 with the more amenable Motion Picture Association of America ratings board. Andy Warhol’s experiments in pansexual movies and other cheapo exploitation films were shown to be worldwide box office gold, so Hollywood took heed. Midnight Cowboy (1969) was set in the seedy world of Times Square hustlers and became the first adults-only X certificate film to win an Oscar – and remains the only X-rated film to win a Best Picture Oscar. Despite accusations of homophobia, many still claim Midnight Cowboy as a revolutionary, gay love story. Hollywood was growing up. It seemed that virtually any subject could be tackled. Luchino Visconti’s 1969 The Damned, for instance, showed crossdressing, rape, incest, paedophilia, and homosexuality, and was quickly followed by the director’s controversial Death in Venice (1971). The subject here was the desire of a dying composer for a teenage boy.

The gripping, recent documentary The Most Beautiful Boy in the World (2021) showed how the actor who had played the young man, Bjorn Andresen, was horribly exploited and struggled to cope with sudden fame.

And then there was William Friedkin’s The Boys in the Band (1970) (it was remade recently thanks to showrunner Ryan Murphy for Netflix). This was the first openly gay film from a gay writer with a predominantly gay cast. Based on a 1968 play, its pre-Stonewall view of gay life was damned by early activists who were appalled by the negative stereotypes. Yes, the film did depict a self-hating gay lifestyle that existed, but there was something to be said about letting a festering wound breathe fresh air. Arguably, the movie provided something to kick against, and it opened a door for other gay movies… although the wave of New Queer Cinema would have to wait until the early-1990s.

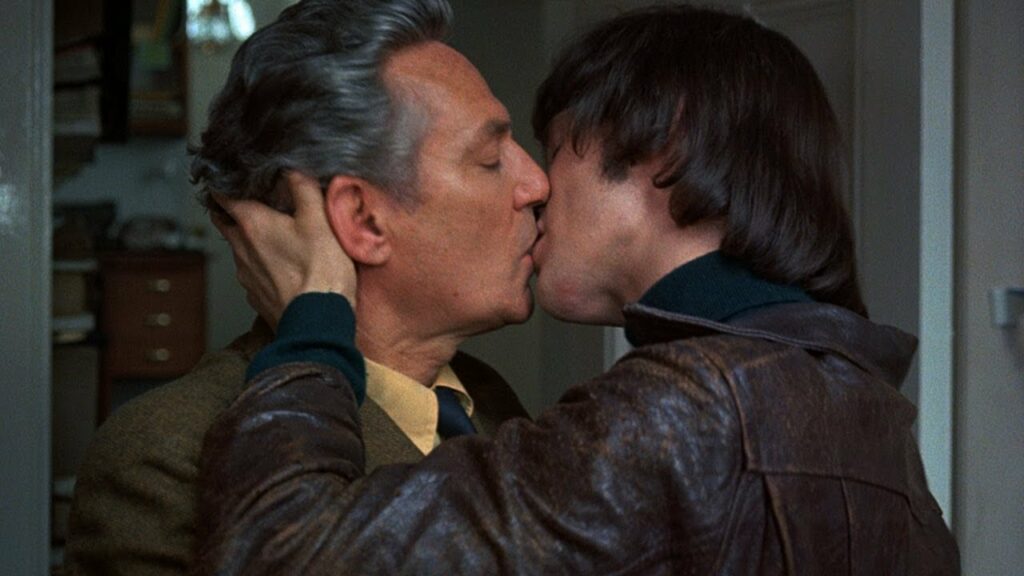

And while a scene in Boys of two men kissing ended up on the cutting room floor, gay director John Schlesinger’s Sunday, Bloody Sunday (1972) was famous for its kiss between two men. Advances in gay rights in the 1970s and 80s saw the Queer Code be broken. This new LGBT+ visibility saw a raft of movies that were unapologetic in their depictions of queer characters, like Making Love (1982) and Desert Hearts (1985). The era of Queer Coding was ostensibly over in the West.