That the midnight screening for Lux Æterna – Gaspar Noé’s 50-minute quasi-advert for Yves Saint Laurent – was undoubtedly the highlight of Cannes 2019, says something. In a year that featured Parasite, Portrait of a Lady on Fire, The Lighthouse and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (Jesus Fucking Christ), this little cocaine bomb of an essay film set this reviewer’s heart on fire more than anything else. Beginning around an hour late to raucous applause, copious booing, and a chain-smoking cast who appeared drugged out of their minds, and ending with a standing ovation, tears, and paramedics, Noé’s essay-cum-mockumentary-cum-trip-cum-religious-experience is a wild, ecstatic piece of work that defies explanation and categorisation. And now, three very strange years later, it’s finally coming to UK cinemas.

Lux Æterna opens with a provocative, mysterious quote from Dostoyevsky – “You all, healthy people, can’t imagine the happiness which we epileptics feel during the second before our fit… I don’t know if this felicity lasts for seconds, hours or months, but believe me, I would not exchange it for all the joys that life may bring.” – before segueing straight to a film set. This is where we meet Béatrice Dalle and Charlotte Gainsbourg (starring as themselves).

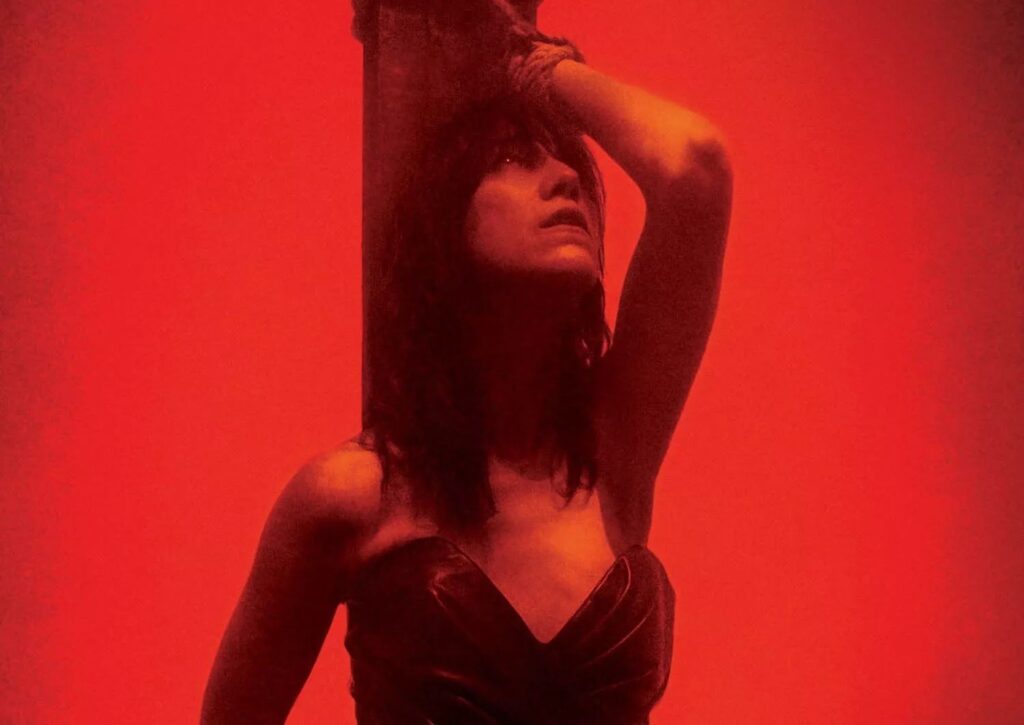

Dalle has transitioned from acting to a directing role and has cast Gainsbourg in her latest movie – something that involves a climactic stake-burning scene. In delicious, delirious split-screen, the two actors quip and chat hilariously about the sexuality and agony of witch burning. But, shortly after this, and bookended by a series of quotes about the artistic warfare of filmmaking from Jean-Luc Godard, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and Carl Theodor Dreyer amongst others, we find out that the production of Dalle’s film is not to be so smooth after all. Conflicts, egos, and disasters both preventable and not threaten to annihilate the project altogether.

As Benoit Debie’s signature camera weaves and soars through the artificial wooden confines of a low-lit neon set, chaos is rife. A producer is trying to get Dalle fired, and to have another director step in; an over-excited young filmmaker is repeatedly harassing Gainsbourg about his new film; none of the young stars (including a brilliant and self-parodic Abbey Lee) seem to be able to figure out what the hell is going on; Gainsbourg receives a frantic, ambiguous call from home that suggests her young daughter has been sexually mutilated. Her intense distress filters both into her irritability and traumatised performance.

But then, in the midst of this shouty, cacophonous degeneracy, something starts happening. An LCD screen displaying flames begins to strobe uncontrollably. At first, the cast and crew try to stop it, but they quickly become captured and transfixed by the light. Like those magic eye pictures from the 80’s, Noé’s double and triple-screen images begin to coalesce and blend under the assault of colour into three-dimensional, illusory and undefinable spectres that writhe and dance in the dead-space between the naked eye and the screen.

In the muffled sensory deprivation of the cinema, the only stable reference-point is the screen, so when Noé begins to expand and contract his aspect ratio, continuously duplicating, then halving, then tripling his images, all sense of time and space begins to warp and evaporate. Sitting there in the Lumière in 2019, I began to feel as if falling through some strange, psychedelic void untethered from reality.

The strobing continues and continues, drawing the audience closer and closer into the shape-shifting screen as barely existing stroboscopic shapes and illusions emerge from the subconscious fog. Vision begins to fade away at the edges as consciousness – or at least some form of consciousness – slips away from under the viewer’s feet. It is your choice whether to accept the invitation, or to resist. By accepting, you agree to free-fall through this technicolour chasm of light and sound and colour where something magical, undefinable and mysterious appears – the spectre of Werner Herzog’s ‘ecstatic truth’ in its purest form. This is Cinema – quadruple distilled to navy strength then downed straight from the bottle. Pitching forward into subconscious space, its deistic face looms forward from the primordial ooze for a moment that simultaneously feels like an eternity. The spirit of creation staring back at creator, created and receiver alike – the force that drives human progress separated from its fruits in a move that feels as elementally terrifying and beautiful as the splitting of the atom.

“Thank God I’m an atheist” reads the title card that snaps the audience out of the trance – and, more than just an amusing wordplay, the line makes perfect lucid and revelatory sense. Some leapt to their feet with roaring applause, others seemed too stunned to move, others looked on in disbelief and bewilderment, and others still had already left.

I’m not sure if I’ve explained Lux Æterna well – I’m not sure if it’s even possible to explain – but this is a film which successfully conjures a quasi-religious experience of transcendence that left me wide-eyed and gaping for the next hour. Filmmaking is alchemy: out of such disparity and conflict comes something with a mythical, magnetic force. It is creation – Godlike – from nothing. Film is not the sum of its parts, for its parts do not add up – but a primal energy soaring electric through the darkness. That night, its euphoric lightning struck the Theatre Lumière with such force that the building threatened to spontaneously combust. And now, dear reader, you can experience it too.

A line in the still-stroboscopic credits reminds us that, yes, this thing was made for Yves Saint Laurent.

Lux Æterna releases in cinemas from May 30th.