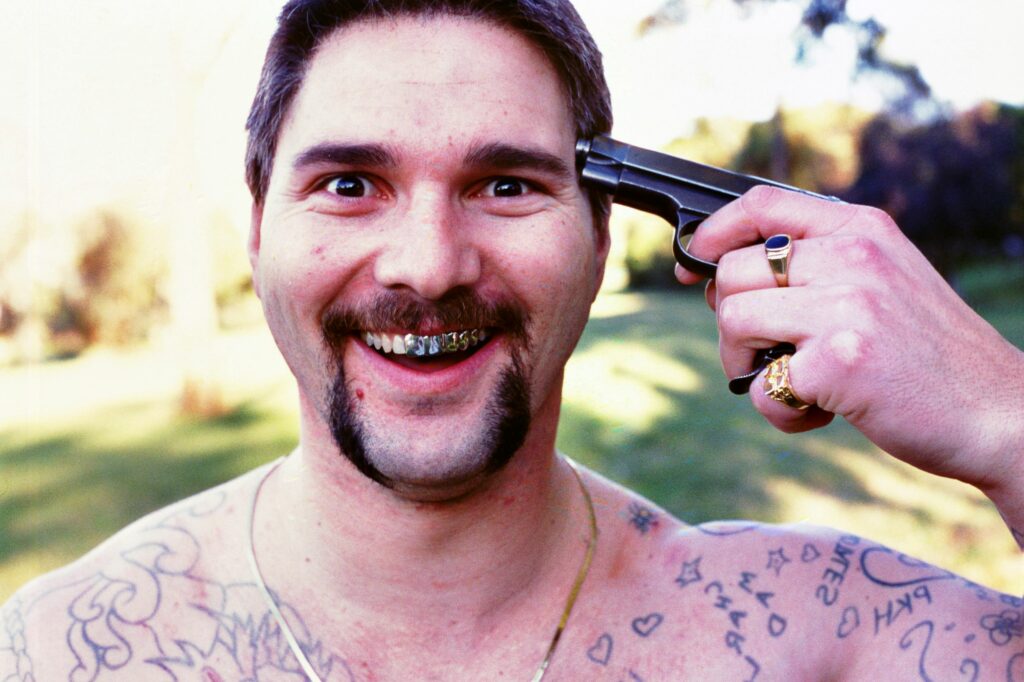

Based on the real-life exploits of Australia’s most infamous criminal, Mark ‘Chopper’ Read, the brand new and remastered version of crime classic Chopper is being re-released in key cinemas and on digital platforms.

First released in 2000, the award-winning smash hit debut from writer-director Andrew Dominik featured Eric Bana in his breakout role. Dominik would go on to direct the acclaimed The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, Killing Them Softly, Mindhunter, and the upcoming Marilyn Monroe-inspired Blonde starring Ana de Armas.

Now, some two decades on, Outtake speaks with Dominik about the film’s legacy, his first-hand experiences with Mark Read, and finding the heart of Chopper.

Do you remember what convinced you to adapt Mark Read’s story to film?

Andrew Dominik: He’s funny. The thing that really got me was the whole ‘I regret nothing’ stance that he took, but that he’d also describe the faces of his victims coming back to him in dreams. I sensed that there was sort of more to it than what was in the books [Read’s bestselling autobiographies]. But the books were hilarious, the first one in particular.

That sense you had that there was more to it, did that mostly emerge when you first met him?

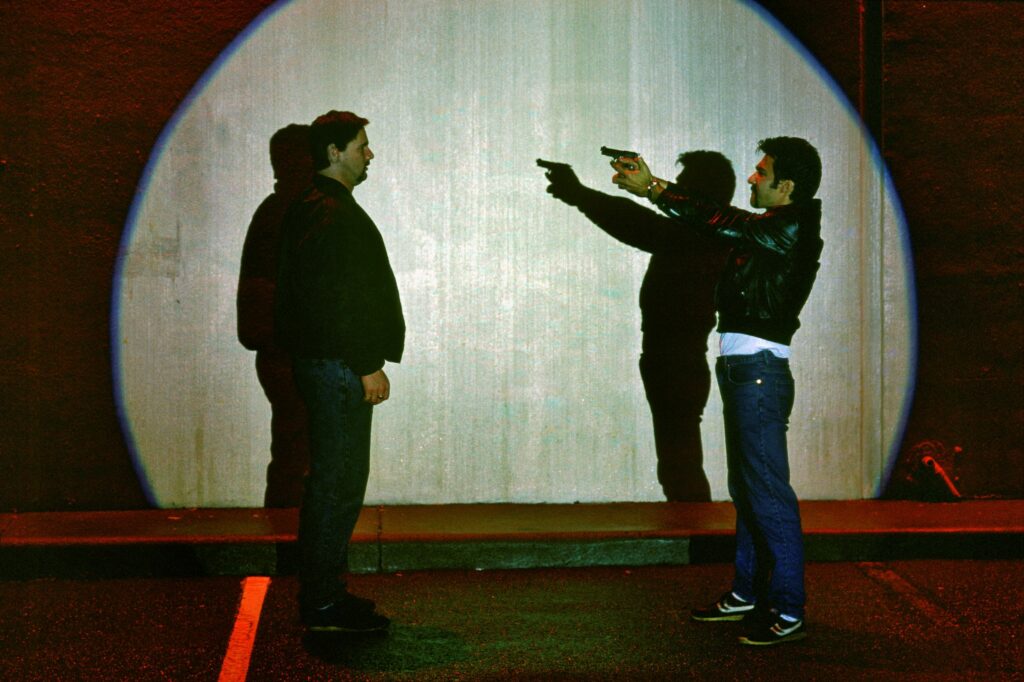

Andrew Dominik: No, I didn’t meet him for a good five years. I tried to. When I started with a first draft of the script, it was just a superficial gangster film of the kind that were around a lot at the time – you know, Quentin Tarantino movies, Guy Ritchie movies. I felt like what I’d done was a bit thin. I think a friend of mine actually told me that I was just like a middle-class guy jerking off to fantasy violence. Which, you know, was fair enough.

So then I went down [Read’s] arrest docket at the back of the book, and I started talking to the police that had arrested him. A very different picture of him then started to emerge. The best thing I found was that these two cops were accused of police corruption by Mark – they’re the ones portrayed in the movie, the ones that had a game of green light. And because of this, Mark’s behaviour for the subsequent six months was investigated by the internal services of the Australian police. They had account for everything he’d done in that six months period. There would be incidents, and they would have spoken to everyone there and you’d get a whole bunch of conflicting reports about what happened.

One thing that became clear though, was that his behaviour was crazy. Like he would shoot people and then take them to the hospital; he was really erratic and all over the joint. It was about having to make emotional sense of that, that’s what the movie became. Then of course, there were photographs I had of him where you could see the pain in the guy’s face. He was not happy. And when I finally met him in prison, in Tasmania, that was amazing. He was very emotional. He was somebody that was just caught in his feelings, and that really gave me a sense of who he was.

Was there anything that really surprised you when you first met him which you hadn’t anticipated from your research?

Andrew Dominik: There was something grandmotherly about Mark. There was a certain offence that he would take that reminded me of grandmotherly offence, you know. Maybe it was his mother’s voice in him or something. His mother was kind of a horror, from what I could gather; she was violent towards him and was the instigator of all violence that was directed towards him as a child, whether it was dished out by his father or by her. There was something feminine about his rage, if that makes any sense.

It’s a thing that I’ve noticed. Like Kenny Graham, who plays Mark’s father in the film, he’s playing his own father. People carry the internal voice of their abuser. That’s why the best people to play prison guards are prisoners because they’ve internalised that voice. In fact, that’s what you see in Chopper. The prison guards will come in and play prison guards, and they would play them like they were Bruce Wayne, or Clark Kent. But then you get prisoners to play prison guards and they’ll play them like assholes.

So there was a feminine component to Mark’s rage, to that voice within him that hates.

I suppose that’s not something you could pick up from anywhere except speaking to him face-to-face.

Andrew Dominik: Completely. You can have every opinion about a person, but when you’re sitting there and they’re fully fleshed out, and you can feel their emotional forcefield, that’s a wholly different experience.

I mean, he’s a human being. Aspects of Mark were very frightening, don’t get me wrong. I remember when Eric [Bana] and I went down to spend a weekend with him on his farm in Tasmania, after he’d just gotten out of jail. It was so stressful that when I came back, I slept for three days. I think Eric and I fell asleep on the plane back.

Were you worried that he might behave erratically?

Andrew Dominik: Mark has a way of making you feel like he’s doing you a favour by not killing you.

He’s completely erratic in person. But so funny. And that video tape I made of him on that weekend away, I would just put that on – it was like four or six hours of video – and I’d watch the whole thing. Just sit there and watch everything he says, because it’s just so compelling. But it was pretty scary to be sitting there. He’d give us plenty of demonstrations, too, like “and this is how you stab a guy in the face!” [Laughs].

Chopper was also the target of some controversy when it came out, because of its subject and because of how the film is very much on his side in exploring his trauma. What was your intention in how you wanted to represent him?

Andrew Dominik: The film is made completely with love. It’s not blind to Mark’s failings as a human being, we see Mark do all kinds of shit where he’s completely overreacting. He’s not in the right! But it’s very much made with love.

Was that always your intention with the script, or is that something that changed when you got to know him?

Andrew Dominik: I mean, I think it’s pretty hard to make a movie about a person you don’t care about. And I guess what I was interested in was, what are the consequences of violence for the violent? What do the violent suffer? They’re the ones that are the problem, not the victims. And I was just interested in that.

It also became apparent that he had very mixed feelings about his behaviour. He found his own behaviour disturbing, but he wasn’t in control of it. It’s like that for a lot of people, I feel.

Did you come away with any insights about those questions of violence at large?

Andrew Dominik: I think the consequences of violence for the violent is loneliness. The interesting thing about Mark is that if he’s hurt you, he’ll do it again. It’s like he wants to hit the guilt, hit the bad feeling. But if you hurt him, he kind of accepts it.

And I found this throughout his life. People who’d hurt him, he wouldn’t retaliate against – I’m talking about physical violence. If you were to betray him, he’ll go off. But if you stab him, that’s fair enough.

Apparently, psychoanalytic theory is that guilt develops from a very primitive fear of retribution. So if a baby has a hostile thought towards its mother, it thinks “if my mother knew what I was thinking she’d let me get hurt.” And that’s the beginning of a guilt feeling, which is going to turn into being able to play well with others. But as a result of being traumatised at a young age, he just got stuck there, and he’s trying to develop those processes. He doesn’t feel guilty because he’s attacking people, he’s attacking people in order to feel guilt. That’s the way it was explained to me by a shrink. Chopper isn’t necessarily that kind of movie, but the behaviour does ring true.

And now, some twenty years later, it’s interesting how the film’s become ingrained in the cultural lexicon. Do you remember a specific instance when you saw Chopper referenced in other media, that made you realise how wide-reaching it had become?

Andrew Dominik: It was a political cartoon during the Gulf War. It was called Australia Lends Support, and it showed the prime minister on the phone to the American president, saying “not choppers, Bill, I’m sending Chopper!” I liked that. And I like that guy who does Chopper’s weather report. Some of them are really funny.

And what was Mark Read’s reaction to the finished film when he first saw it?

Andrew Dominik: He watched it through the door from the kitchen, as it was playing on his TV. He said, “you must be psychic. Who did you talk to?” He felt that it was 98% accurate, and he said that watching himself from the outside made him reconsider a lot of what he’d done.

Like an out-of-body experience…

Andrew Dominik: That’s actually what he told me when I started. That he wanted to see how someone else saw him. I took him at his word on that. But I also did a whole lot of things he told me not to do, so I was pretty worried.

Things like what?

Andrew Dominik: He didn’t want to be seen taking drugs, even though he was a sweet freak. Because that was his whole anti-drug stance that he had in the books – that he was like a Batman, cleaning up the baddies. Also, no violence against women. That was something I knew he’d done. And no poems. Mark was always writing little poems. But all three of those things were in the film.

I mean, the drugs and beating up Sharon were the worst offences in terms of how Mark reacted to them being included in the film.

It’s strange that he was known for lying about a lot of things yet was so interested in having a film made about himself. It’s almost as though he was asking you to challenge his own self-image.

Andrew Dominik: Maybe. That’s what he said but whether he was serious or not, it’s hard to know. But he didn’t seem to freak the fuck out about it!

That must’ve been a relief.

Andrew Dominik: Oh my God, you have no idea. It was terrifying.

Chopper releases in key cinemas and on digital platforms from March 25th, 2022.