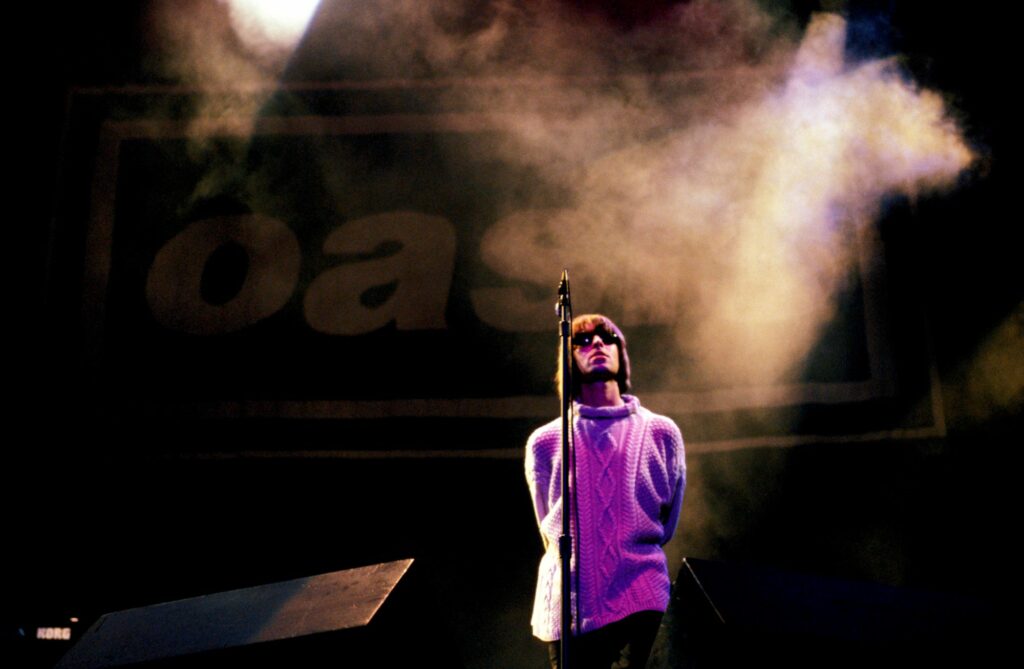

Directed by Grammy Award-winner Jake Scott (son of director Ridley Scott), Oasis Knebworth 1996 is a joyful, thrilling, at times poignant celebration of one of the most important concert events of the last quarter-century. Driven by Oasis’ music and their fans’ experiences of that weekend, and build around never-before-seen archive and backstage footage, Scott’s concert film immerses the viewer completely in this monumental musical event.

Ahead of the film’s release, Outtake spoke with director Jake Scott about the making of the documentary, Oasis’ cultural significance, and the special relationship the band had with their fans.

How did you come to direct Oasis Knebworth 1996 ?

Jake Scott: My producer Garfield [Kempton] in London is friends with Alec McKinlay, who managed Oasis then and manages Noel [Gallagher] now. And Alec asked Garfield to see what I thought of directing it, so it came to me that way. That was last year in June, when we were all sitting at home and staring at the wall, and I had just seen Supersonic and really enjoyed it. I’d never done a concert film before – albeit with someone else’s footage – but I had a look at some of the footage and was really impressed with what they’d gotten. And I’m glad I did because it’s been brilliant.

And I’d imagine the amount of footage is extensive, so can you walk me through your methodology for selecting and organising footage?

Jake Scott: It was many hours sitting with Struan Clay going through every single file. What’s interesting is that you start to identify certain people, thanks to their proximity to a certain camera position. Then it’s about finding the links between what you’re seeing and what you’re hearing from the fans’ accounts. It’s a bit like making lasagne: you put layer after layer, after layer.

Some things didn’t work, and you go back and try another route. We stuck to our guns though, with regard to telling the story through the fans and experiencing Knebworth through the fans. I really wanted it to be a fan’s account of being there, making it as experiential as I possibly could.

So that’s why we don’t cut away to a fan who’s now in their 40s and sitting at home, talking about that weekend 25 years ago. You wanted to keep the audience there. And the footage allowed for that; it had been shot in many different formats, from handycams, broadcast-quality cameras, Super 8, 16mm film, etc. On the big screen, some of it does turn out a little underexposed, some of it’s a bit grainy, but it’s all part of the film’s texture and the quality of film. I love it because it’s very much part of the time and the period.

But really, it’s a process of identifying these connections. One of the big decisions we had to make was, “do we make it a mix of the two nights and show it as one concert?”. But I felt that there was a distinction between the two nights, so we stuck to our guns and went for it, showing day one and then day two. You build up the anticipation for the first night, you get that high as the night happens, then the comedown, and then the next morning you’re in it again.

If you wanted to immerse the viewer in what the experience would have been had they been there, in-person, then why did you decide to make it Day 1 and then Day 2? Since fans would only attend either one or the other.

Jake Scott: Great question. It was because it did take place over a weekend, and there was a difference between the two nights. The first night, the band and their performance have a different quality. There’s a lot more swagger in the second night, so it built nicely. I don’t want people who went to the first night to think they missed something the second [laughs], but this is immersive because you’re a fly on the wall at both nights! You got tickets to both nights, how about that?

Good selling point. In that same vein of wanting that ‘fly on the wall’ quality, why then decide to conduct retrospective interviews with fans who attended – even if those interviews do happen off-camera?

Jake Scott: I love the audience. I fell in love with the idea of that audience, I love those faces, I love the eagerness, I love them. The epiphanies you’re seeing and that light in their eyes – 2.6 million people applied for tickets, right? And people came from beyond the British Isles. So, I felt it was nice to hear the voices from all those different regions, as far as we could. We also wanted there to be some emotional context to the concert, and some of the fans’ stories are quite poignant.

For a lot of the people telling those stories, this was a high point in their youth. I thought that was really beautiful too, just to see the power of music, what it can do for people and how it can bring them together. At its foundation, it is an emotional thing… something about the human connection between the crowd and the band, there’s a symbiotic thing that happens. The energy that’s created is a lovely thing to experience, and to work with.

I’ve been asked what I was looking at, if I was referring back to any other concert films. And the film I kept going back to wasn’t even a rock and roll film, it was Jazz On A Summer’s Day by Bert Stern – on the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival, which is a wonderful film. And that really does look at the fans and identify those personalities in the crowd. So Oasis Knebworth 1996 was an opportunity to do that in the context of a rock and roll film.

Focusing on the relationship between fans and the band is interesting too, because it highlights how crowds are as much a part of a festival experience as what’s happening on stage.

Jake Scott: Absolutely. One of the things we did to elevate that – and this is thanks to our very good sound design team – is we actually created a lot of different crowd sounds and we layered that into the soundtrack. It put a lot of perspective on things. And if you watch this with a surround sound system, like you have if you see it in cinemas, you’ll feel that more. It’s spatially dynamic, because you’re hearing voices in the crowd, you’re hearing someone singing in the front row, it’s all in there. You’re feeling the presence of fans around you much more than you normally would. As they say in Spinal Tap, we turn it up to 11.

You touch on this in the film, but how would you describe the ways in which Oasis became such a symbol of the times for Britain?

Jake Scott: Possibly more than any other band. At the time, there was Britpop, Cool Britannia, etc. but at the time, I always felt like they were apart from the Britpop thing. They somehow rose above all that to become – at least for a time – the most important band in the country, and maybe in the world. A lot of it comes down to Noel’s lyrics and to Liam’s delivery of those lyrics, and his swagger and innate rock ‘n’ roll-ness.

But they were five lads from two council estates in Manchester, who are like their audience; and their audience are like them. I feel like, for a lot of young people, it was the first time that they felt like they were being heard and actually had a voice through those songs. There was suddenly a youth culture with renewed optimism and hope after years of Conservative governments. Those working-class lads gave a voice to a whole generation, and that’s a big part of their enduring appeal.

Noel says it in the film, “we were a mirror of the audience, and vice versa.” And as one of the fans at the beginning puts it, “Liam is our rock God. He’s for us.” And that’s such a nice way of putting it. They seemed to shun the superstar thing and retained their connection to their working-class background. I’ve always really appreciated that.

Oasis Knebworth 1996 releases in cinemas worldwide from Thursday 23rd September.