RoboCop, the science fiction classic from Paul Verhoeven, has taken its rightful place as one the defining films of the 1980s. The tagline says all you need to know about the flick: “part man, part machine, all cop.” It sounds like the product of a ten-year-old boy’s feverish imagination going into overdrive. And before the film’s release, that was part of the problem.

Jack Matthews, writing in The Los Angeles Times, called ‘RoboCop’ a terrible title, saying adults would struggle to take it seriously. Also cause for concern was Verhoeven himself not understanding the story’s satirical edge, that is until his wife Martine convinced him to take it on. But it proved to be a hit, and that giddy silliness is part of the film’s charm. RoboCop can stake a serious claim as the smartest dumb movie ever made, not only for what it says about the human condition, technology, and politics… but about the police.

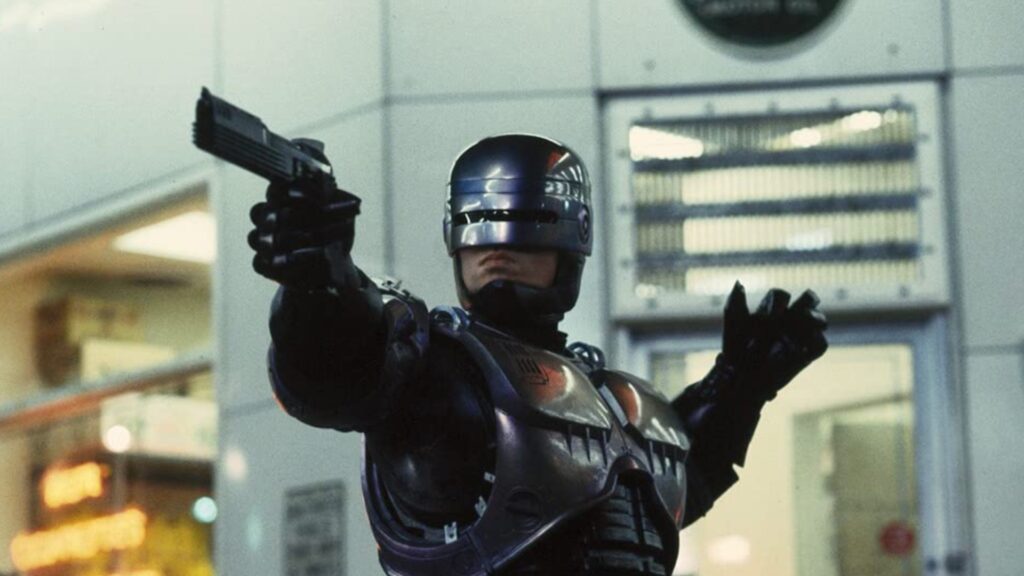

There’s no point skating around the obvious. The ultra-violent RoboCop is bloody, funny and full of bumbling cyberpunk charm. It is full of iconic dialogue, with Paul Weller’s performance as the titular supercop somehow grinding out charm and sass through a monotone voice. The visual effects are, for a post-Star Wars Hollywood, so ingeniously ham-fisted, adding to RoboCop’s unavoidably comedic flavour. And the comically grotesque violence is as funny as it is disgusting. On a superficial level, RoboCop has all the glorious appeal of a cult classic: a cocktail of senseless violence and crude humour, in the loyal service of celebrating America’s finest in the quirkiest, most dystopian way possible.

Except it is more than that, and it is far from the unquestioning celebration of the badge that it first seems to be. A lot has already been written about how RoboCop is a rebuke of Reaganomics and unjust corporate power. Also addressed have been the film’s commentaries on gender and philosophical discussions of exactly what constitutes a full human being, most strikingly observed through Murphy’s struggle with his identity after his pretty extreme ‘cosmetic surgery.’ But the representation of the police is another fascinating focal point in the film and one that, if anything, has found renewed relevance in the years since RoboCop’s release.

The police in RoboCop, set in the year 2028 (but which in reality is just the 1980s with shinier tech and fewer shoulder pads), are at the whim of capitalism. Specifically, the city of Detroit have entrusted management of the DCPD to Omni Consumer Products (OCP), their hand forced by dwindling resources and skyrocketing crime rates. It is a young OCP upstart, Bob Morton, who first thinks of RoboCop – a new weapon in the fight against crime. OCP is quickly shown to be an organisation dripping in prejudice, corruption, and greed, sins which disseminate their way down to the police department they are now charged with running.

In comes Officer Murphy, who has been transferred to the Metro West precinct – “welcome to hell” as one of his new colleagues puts it. Unknown to him, OCP have transferred him and multiple other officers to the frontline in the expectation that one of them will be killed – and become an unwitting subject in the RoboCop programme. So it comes to pass, and Murphy becomes the ultimate weapon in law enforcement after he is brutally gunned down by a criminal gang.

In RoboCop, the police as an institution is poisoned. It is poisoned by greed, mismanagement and callousness. With OCP in the driving seat, the DCPD become an enforcer of gentrification and indiscriminate force. It is OCP’s meteoric rise to power that is to blame for the social decay of Detroit, which the company basically wants to bulldoze and reinvent from scratch. “Old Detroit is a cancer,” as the OCP Chairman puts it, failing to recognise his role in the slow death of the city. The moral apathy at the heart of the police comes to a head when the force are ordered to gun down RoboCop, one of their own, on the orders of OCP Senior President Dick Jones. It is not a bloody scene, certainly not when compared to Murphy’s earlier death scene, but it is still brutal. Mercilessly gunning down a fellow officer in this manner highlights how the DCPD have lost their moral authority over Detroit. They blindly follow orders rather than upholding any kind of lawful or ethical code. The result, sadly and unsurprisingly, is a city rife with violence which RoboCop himself can barely contain.

If there is any goodness to be found in the police, RoboCop tells us that it is found at an individual, rather than institutional, level. Before his death, Murphy is somewhat cocky but undoubtedly a good person, determined to do right by his community. During his earliest outings as RoboCop, Murphy is as robotic and obedient as any other officer, with only faint glimmers of the original maverick man behind the metal. With time however, Murphy rediscovers his humanity, and couples what he has gained with what he has lost. In one striking scene, RoboCop revisits his old home (which is now up for sale) and has flashbacks of his wife and son. Overcome with sadness, Murphy slowly rediscovers what it is to be a man, a father, and a cop. It is this personal journey that leads him to triumph both against the criminals who killed him and against the OCP executives who turned him into a half-man, half-machine.

What does this say about the police? That if there is any virtue carried in the badge, it is found at the level of the individual – not the police as an entity of justice, an institution, or vehicle of corporate influence. As a collective the police in Detroit are almost beyond saving. But RoboCop has, (somewhat ironically) by sacrificing key physical markers of his humanity, rediscovered the soul that his fellow officers lack. Even in the scene where he has beaten Clarence Boddicker to a pulp, and could very easily kill him, his principles to uphold the law and not to attack those who cannot defend themselves guides him to do the right thing. Boddicker is spared, and arrested, after which the corruption inside the DCPD and in OCP allows him to be released. Murphy is dedicated to what is good and right, a dedication shared by his partner Officer Lewis (Nancy Allen, who can never get enough credit for her contribution to RoboCop’s legacy). Together, they represent the goodness that the police should embody, but cannot.

Exactly where ‘goodness’ in the police lies is a question film and television has grappled with for some time, increasingly so since the murder of George Floyd and many others at the hands of those meant to keep the public safe. To say that all depictions of the police before this were flattering however, is of course untrue, as anybody who has seen The French Connection will tell you; documentaries like Ultraviolence have also shone a light on police brutality and failure. But amidst the endless slew of pro-police TV hits like The Wire, Line of Duty and The Bill (the latter of which is reportedly getting some new seasons), this message can easily be lost. Most recently, Brooklyn Nine-Nine has done an admirable job of trying to lay the problems bare, and like RoboCop it addresses these themes with a comic edge that seems to accentuate the purpose behind the farce. Even if individual police officers mean well, the way that the police orientate and organise themselves means that things like accountability, responsibility and justice within the force are rarely administered fairly. RoboCop is an earlier example of this kind of thinking; to look at the police holistically is damning.

RoboCop is in many ways a model hero; someone who relentlessly pursues what is right and bringing those who do wrong to justice. But behind the jokes, the violence and scenes which have gone down in cult movie history, RoboCop manages to question the righteousness behind this endeavour. Bland ‘copaganda’ this is not, no matter how much the ridiculous title and tagline seem to suggest otherwise. Veroheven’s dystopian masterpiece is instead an insight into how easily forces of good can lose their way. Any positive moral authority in the DCPD is found at an individual level, not an organisational one. It is a necessarily harsh indictment of judicial and corporate ineptitude and structural violence, a syndrome that only the mighty RoboCop can resolve.

The 4K restoration of RoboCop is in cinemas from 20th May.