I first saw the trailer for The Novice in the cinema, a few weeks before I caught the actual film. For context: I was feeling buoyed by the thrill of drinking a fancy ale from the bar—I grew up in a suburban commuter town offering only big chain cinema fare aka rancid ‘nachos’. This buoyancy, and my anticipation of the jocularity promised by Sean Baker’s Red Rocket, led me to make a cutting joke that Lauren Hadaway’s psychological rowing drama resembled a ‘Black Swan for normies’. My friends laughed and I felt smug, but secretly I was intrigued.

Last year I was studying at a university prized for its rowing team. I even dipped my oar in and, although the novelty of five AM starts soon wore off and the allure of my bed grew with the onset of winter, I felt I could instinctively relate to The Novice’s protagonist: a female college student steeped in a self-imposed, neurotic gloom; striving for perfection… With the combination of a brooding Isabelle Fuhrman (Orphan) at the helm and a grittier portrayal of one of the ‘posh’ university sports, The Novice seemed to have potential as an atypical take on the obsessive, overachieving athlete.

The Novice’s opening credits fade seamlessly into a lofty aerial shot of what appears to be a minute, white bird’s claw amongst a sea of black. As the camera spirals downward, it becomes apparent that the claw is actually a narrow rowing boat, with two sculls (oars) protruding over the sides. The striking darkness and inky colouring of this first scene is carried through the entire film, evoking a sense of immersive foreboding.

Yet this shot also reminded me of something I’d seen before. In these first moments, an arresting, frantic, string-loaded original score by Alex Weston is swathed in Todd Martin’s richly symbolic cinematography. Darkness and chinks of light reflecting on the water act as a canvas for a portrait of The Novice’s protagonist, Alex Dall, to be sketched out beneath the bird’s eye, predatory glare of the camera as if tarred by a black, wet brush. The almost monochrome palette, choice lighting and string accompaniment is reminiscent of the opening scene of Darren Aronofsky’s contemporary cult film Black Swan, in which the increasingly disturbed ballet dancer, Nina (Natalie Portman), pirouettes across a shadowy stage while her white tulle skirts are licked by the spotlight.

This isn’t where the similarities end, either. Both Nina in Black Swan and Hadaway’s Alex become suffocated by their desires to be the best at what they do. For Nina, this means securing and performing the roles of both the pure White Swan and the seductive Black Swan of the Swan Lake ballet. For Alex, a student who takes tests multiple times because she chose to major in her worst subject, it means striving to break into the varsity 1V rowing team.

However, while Nina’s motivation for ascending to prima ballerina is charted by her fixation upon ageing star, Beth—she’s shown gazing at Beth on a billboard in one of the very first scenes—and inherited ambition from her mother, Alex’s determination to climb the ranks of the rowing team is not manifestly clear. When one of her coaches (Jonathan Cherry) asks the novice rowers why they’ve signed up for practice, Alex is dumbstruck after gazing into one of the gym room’s many mirrors (another Black Swan motif) and is saved only by a stampede of seniors come to demo for the newbies.

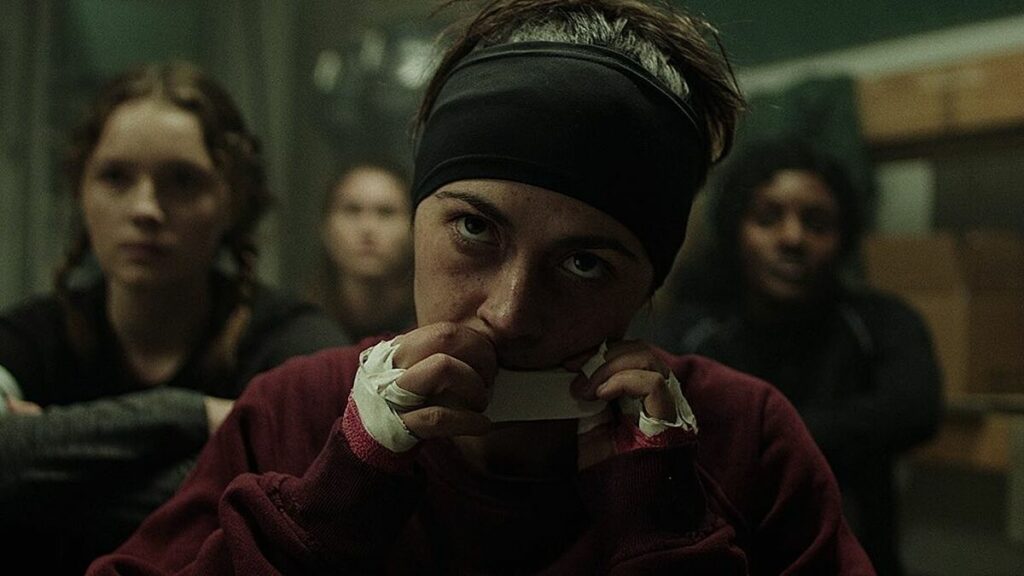

Like Nina, Alex isolates herself from her peers. Where Nina bandages her bleeding feet, Alex wraps her blistering hands, bloody with friction burns from the erg machine and oars. Both of them unravel (literally and figuratively). The motif of reflection—light on the stage/water—and of mirrors is prominent in both films. In an early training sequence, Alex reads a sign posted above a mirror in the gym: ‘remember your competition’. Nina is constantly haunted by her reflection in Black Swan; whether the victim of presumed bullying when ‘whore’ is scrawled on her dressing room vanity mirror in lipstick, or one of the hundreds of times she gazes at herself only to see a malevolent twin staring back at her.

Despite Nina and Alex working themselves to mental and physical exhaustion, they both repeatedly fall short of perfection. Their foils are manifested as Lily (played by Mila Kunis) and Jamie (Amy Forsyth); athletes championed by dance company directors and rowing coaches for their natural flair. Lily and Jamie both attempt to befriend the films’ protagonists early on and excel in performing easy airs which jar with the stunted awkwardness of the main characters. Yet the women’s friendly intentions are called into question when a pre-performance club-night for Nina and a fiercely contested boat race for Alex are revealed as orchestrations of their frenemies in an attempt to sabotage their success.

Oh and if that weren’t enough—the swans of Black Swan also have their foil in The Novice’s rowing team mascot: the raven. When Alex’s brain noise reaches a cacophonous crescendo—signalled by repetitive mental incantations—Todd Martin’s use of impressionistic cuts of close-up screeching, flapping ravens and plumes of black feathers is redolent of Black Swan cinematographer Matthew Libatique’s creepy glimpses of the feathered bogeyman that stalks Nina around the theatre.

If it seems I’m labouring the point, there’s method to the madness. The clear similarities between the two films warrants analysis beyond broad comparisons. In Black Swan, the sexual tension between Lily and Nina culminates in a raunchy, drug-fuelled sex scene in Nina’s childhood bedroom. For a moment, it seems as though handsy dance director Thomas’ (Vincent Cassel) manipulation of Nina and objectification of Lily might be thwarted by the lesbian lovers coming together. However, Lily’s flat denial of their tryst the following day leaves Nina reeling and simply serves to further undermine her sanity.

Differently, in Hadaway’s feature-length debut, Alex’s Queerness and her relationship with her girlfriend (actress/model Dilone) are presented as a reprieve from the white-knuckle compulsiveness of the rowing scenes. While Alex brushes off an unfulfilling one night stand with a frat boy as an item to check off her college to-do list (simultaneously neutering his power to define her sexuality), the scenes between her and her girlfriend, even when they’re arguing, seem tender and oriented toward a female gaze.

While there is something to be said for complex and even jarring portrayals of Queer sex in film, Black Swan’s ambiguity over whether sex between Lily and Nina actually takes place leaves a lingering air of gratuitous lesbianism catering to a straight male gaze; the audience is positioned similarly to ballet director Thomas’ lustful eye. This same ambiguity also has the disadvantage of leaving the audience to wonder whether Queerness is merely a corollary of Nina’s spiralling grip on reality rather than an authentic component of her character.

Ultimately, where Aronofsky’s iconic but fraught ballet destroys its prima ballerina, directing a whirlwind of violence inward at its climax, The Novice’s conclusion leaves greater room for optimism without coming across as excessively twee. Beyond some niggles with pacing and a little heavy-handed scripting in parts, The Novice is an enjoyable psychodrama which really showcases the potential of its director. Though it never quite manages to reach the sublime fever-pitch of Black Swan, it does chart a fresh course in its handling of Queer romance and obsession. I’m excited to see what Hadaway does next.