From horror movies to creature features, an intriguing if not widely-discussed question underpins monstrosity in film: are monsters ‘under your bed’ or ‘inside your head?’ In other words, are they (or at least could they) be real, or are they a representation of something else? Hollywood, with its dependence on textuality, seems to overwhelmingly favour the latter, following the Psychoanalytic tradition.

Sigmund Freud’s deconstruction of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s The Sandman remains foundational to this (and if you haven’t already seen it, give Paul Berry’s 1991 short film version a watch). Understanding monsters is central to the psychoanalytic lens of film criticism. But is this perhaps a narrow view? When we tell ourselves that Freddy Krueger doesn’t exist, or that there are no maniacal pagan death cults living in near constant daylight in Northern Sweden, what worldview are we accepting? Movies reflect back onto the world that they come from. As fantastical as creatures of death and anomalies of nature can seem, they are no different.

If you’ve ever stopped to ask yourself how you would define a monster, you will likely see a monster as other from you (we would hope so, anyway); they are inhuman and terrifying, the grotesque extreme of the ‘other.’ In his book Monster Theory, J.J. Cohen writes that monsters refuse “to participate in the classificatory order of things” and unnervingly creep towards Freud’s idea of the uncanny (although it is not really his idea – Freud was building on the work of German psychologist Ernst Jentsch). Freud explains that the uncanny can be, for example, wondering if something dead is actually alive or vice-versa, whether something is an animal or human, and so on.

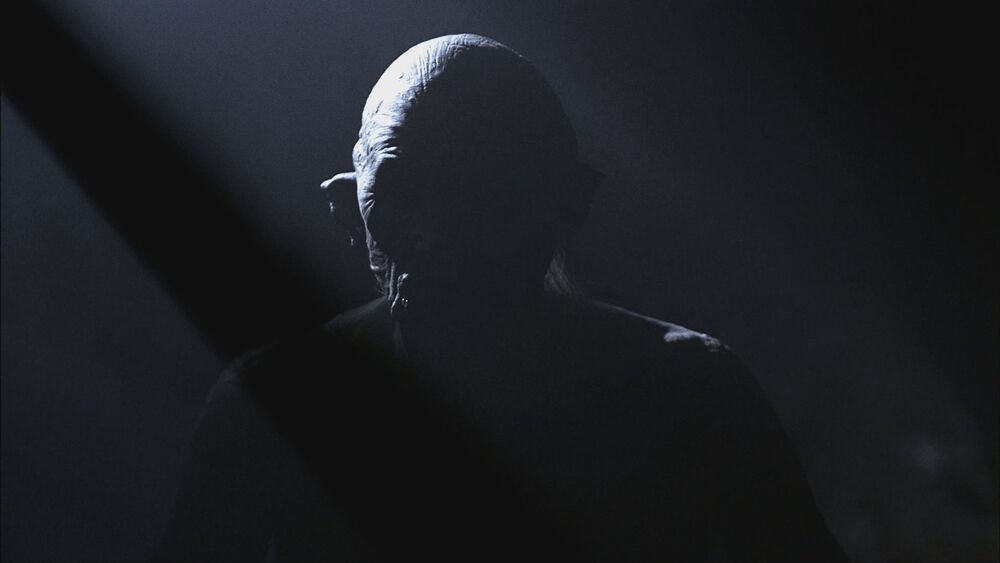

You don’t have to look hard for examples. Zombie movies have played on the uncanny line between life and death for decades, with Frankenstein’s monster one of the earliest examples. Other characters like Halloween‘s Michael Myers or The Terminator franchise’s T-1000 pull off a similar trick in that they are near impossible to kill. Crossing the boundary between the human and animal is clearly exemplified in many ‘monstrous’ beings, from werewolves to the Creature From the Black Lagoon, and the Amphibian Man from The Shape of Water. Exactly how we are made to feel about these people and creatures depends on the story that is then told, but the initial reaction will almost always be one of awe, confusion and – more likely than not – terror. We recognise something that is categorically other, and it’s these reactions of fear, incomprehension and disgust that genre films have relied on for years.

Yet it’s not enough to simply fear the beast. Freud argues that the uncanny figure of The Sandman and how he steals children’s eyes is directly associated with the unconscious fear of castration in children, contextualising the rest of Hoffman’s short story. Psychoanalysis has a rich history of feeding into horror movies in this vein. Repression, sexuality and the uncanny feed into almost all nightmarish beings, from Carrie White to Pennywise. Somehow, and against better judgement, we dare not look away. Pennywise is a sadistic and twisted shadow, yet for this very reason we are drawn to him, for he is quite unlike anyone else. The most famous example is Dracula, whose sexual magnetism and charisma is matched only by his evil intent. Throughout Euro-American media and folklore, the uncanny resurfaces as a device to make figures of monstrosity both repulsive and alluring. Regan from The Exorcist is perhaps the most obvious example, and the whole film is a vindication to the rich textual analysis that the psychoanalytic approach can offer. Writing in Film Quarterly, Noel Carroll identifies a number of sexual connotations in Regan’s actions, from the skin disfigurement resulting from masturbation to the head turning that indicates a witch being sodomised by Satan. It is horrific to watch, yet the very things that make it so distressing are also what make it so intriguing. As a genre, horror is the ultimate medium for exposing the fragile foundations of our ordinary existence, a task with no end that will always find an audience.

Pennywise from Stephen King’s It is another classic example. David Gilmore writes that monsters “are, deep down, tokens of fracture within the human psyche.” Taking the psychoanalytic position even further, Gilmore argues that children see the monster in two ways; as something to be feared, embodying the punishing oedipal parent, and yet also attractively familiar, representing the bad self already present within the child. The child sees the uncanny within the monster, something that fuels King’s story.

What if we told you, monsters are real?

The suggestion that monsters are ‘inside your head’, where you cannot experience them lest you confront the uncanny with your own eyes, has proved a rich tool for textual analysis. Monstrous figures from horror movies have been decoded using this psychoanalytic framework for decades, expanding on what makes horror movies appealing. But it is not without its criticisms. The entire groundwork of psychoanalysis has come under near constant scrutiny, for very good reason – Freud’s drug-driven ramblings resemble wacky storytelling more than they do hard science, in spite of the influences his work has had on modern understandings of the mind. One of psychoanalysis’ biggest issues however, is the deeply-rooted Eurocentrism found to be underpinning it. Even Bronislaw Malinowski, one of the earliest anthropologists and a supporter of Freud’s theories, argued against the universality of psychoanalytic explanations. Using this framework to argue that monsters are ‘inside your head’ is too universalist to feel like a satisfactory answer. It risks limiting one of the most global artforms we have to a very localised means of analysis.

An obvious consequence of this Eurocentric bias to interpreting monsters textually is the insistence that they do not, and cannot exist. Consider the following statements:

Monsters are “established in the mind” – Freud

Horror narratives and their monsters “do not reflect empirical reality but rather the psychology of our species” –Mathias Clasen

Aboriginal ogres are often “a projection of the psychosexual topography” – Ute Eickelkamp

There is an undercurrent of dismissal, even scorn. The writers ensure that the reader, as fantastical and brilliant everything about monsters might seem, is reminded that to believe in their existence is a symptom of delusion. Furthermore, there is a universalism; an apparently scientific insistence that this applies to all people everywhere.

Fortunately, there exists many studies that forgo these limitations, or at least try to. They accept that monsters can form part of reality – they are ‘under your bed’, rather than ‘in your head.’ They are real, material and with consequence for those who share their world with them. Studying the Rock Cree Indians of Northern Manitoba, Robert Brightman seems to take the existence of the ‘witiko’ monster among the Rock Cree Indians of Northern Manitoba as a given, displaying far more interest in documentation and understanding their relationship to the people. The witiko is a subclass of species, no longer human, which is why their hunger for human flesh can only be referred to dubiously as ‘cannibalism.’ Brightman does not explain the witiko in psychoanalytic terms. Instead, everything about the monstrous witiko that Brightman notes – its sharp teeth, taste for raw or roasted human flesh, lack of clothing and a heart of ice – is also what sets it against the Rock Cree and, in turn, defines the Cree themselves.

Other First Nations groups such as Inuits are often associated more closely with witikos by Rock Cree, emphasising how the monster is a means of identity formation. Belief in the very real presence of this monster helps to reinforce what it is to be ‘Cree’. It is fruitless to see the witiko as some kind of internal projection of a Cree person’s mental state. Instead, the Cree accept the existence of the monster as much as they accept their own existence. Its being is a large part of how they understand themselves and others. To dismiss their relationship to these beings is to impose a colonialist mindset on their livelihood, refusing to accept the possibility that their existence is based on different terms. In turn, this exposes how traditional means of horror interpretation are based on foundationally biased ideals.

Joanne Thurman also undermines the suggestion that monsters are purely imaginary, citing fieldwork with the Mak Mak Marranunggu in Litchfield National Park, Australia. they co-exist with numerous different monsters, such as the Nugabig. They are described as “cave men… human-like, but not aboriginal”, drawing immediate comparisons with the witiko. There are also luminous monsters known as the Minmin Lights, and Latharr-ghuns, which are large black dragon-like creatures. Thurman understands these creatures not in terms of the uncanny, but in terms of anomaly. She manages to show that these monsters not only exist to the Mak Mak Marranunggu, but give their world significant meaning. As with the Cree, these creatures exist in relation to how the Mak Mak define themselves. The monsters are awoken by strangers, while only natives can mitigate any threat. It is not the case that “the monster dwells at the gates of difference”, as J.J. Cohen believed, but rather the monsters are a means through which difference itself is understood. Monsters are not the internalised projection of a difference or extreme, but rather they are the mediation of that difference. It is a small but important distinction.

These monsters exist to the native aboriginals, yet not to visitors such as tourists. Thurman explains that while “the national park and the Mak Mak Marranunggu world spatially overlap, visitors to the park are in and of a different world.” While psychoanalysis assumes a shared origin and human experience across cultures and across the world, it can be possible to find yourself “seeing a different world… [to] see country differently and to understand, experientially, the feeling of being a stranger” in a strange land, as Thurman puts it. Rather than the existence of monsters being determined within a universal human experience, they can exist in the world experienced by the Mak Mak Marranunggu without existing in others. The monsters are real, everywhere, timeless and not necessarily to be feared. In horror movies the uncanny is meant to be at least partially scary, as confronting repressed anxieties or anger is seen as a distressing process, but here this is not the case. The sincerity with which Thurman treats these accounts of monsters moves beyond a purely text-based interpretation and sees monsters as being real within a world, but not necessarily all ontologies. The refusal to take experiences of monsters seriously is the most powerful argument against the idea that monsters are illusionary, as it suggests crippling limitations of the ontology and methodology of psychoanalysts, and film critics who are all too happy to apply the concepts. Monsters are under the bed, but only some will be under your bed.

What does this tell us about monster movies and horror flicks?

This is all well and good, but what can these detailed fieldwork reports actually contribute to film criticism? As already mentioned, interpretations of monster movies and horror flicks have thrived off the psychoanalytic suggestion, yet they take little time to explore the wider implications of this theory. The dismissal of monstrosity as imaginative fancy, or of mythical beings as evidence of trauma, has purchase in certain contexts but not all. Instead, anthropological accounts offer an opportunity to recognise cinematic monsters as the border between worlds, and a means through which people come to define themselves and others. Monsters are not different, but difference itself. They are not the ‘other’, but a means to identifying the ‘other’ in relation to yourself. The exploration of your own personhood and your own belonging is central to films – and, significantly, does not contradict the Psychoanalytic tradition, since confronting what may be repressed or feared can still form a substantial part of your personhood.

There are some potential examples even within Euro-American cinema. In Coraline, the world that exists beyond the hidden door in the Pink Palace is real – many children have disappeared over the years. Coraline does not confront some deeply buried fear when she traverses the divide between her world and there, but instead the world (and what she finds there) is an opportunity to find out more about her own being – as a daughter, for example. Similar arguments can be made about A Monster Calls. While Conor’s arc sees him confront a great sadness and anxiety in his life, the monster is the gateway that allows Conor to explore this grief, rather than representing the grief itself. Through the monster’s counsel, he develops an increasing acceptance of his own self and of the fate of those around him.

To see on-screen monstrosity as the border between differences, rather than difference itself, may sound like a minor distinction. However, not only does it pay due credit to those who may experience and relate to the world differently to us, but offers the beginning of a new route of film criticism. One that does not depend on productive but problematic theorisations of the mind, and one that is better equipped to understand how people relate to one another through these key gateways of difference.