Movies in the first half of 2019 have sown a seed that is taking on a multitude of forms. From big blockbusters to indie releases, cinema this year seems determined to usurp the present and bring the 1990s back into our lives. It’s seen in the latest addition to franchises housed firmly in that decade, with both Toy Story and Men in Black getting new entries. It’s seen in the large number of movies set in that time, from one of the biggest films of the year, Captain Marvel, to Jonah Hill’s Mid-90s and the Glasgow-set drama Beats. It can also be seen in the phenomenal modern day success of stars who found their fame two or three decades ago, from Will Smith to Sandra Bullock and Samuel L. Jackson.

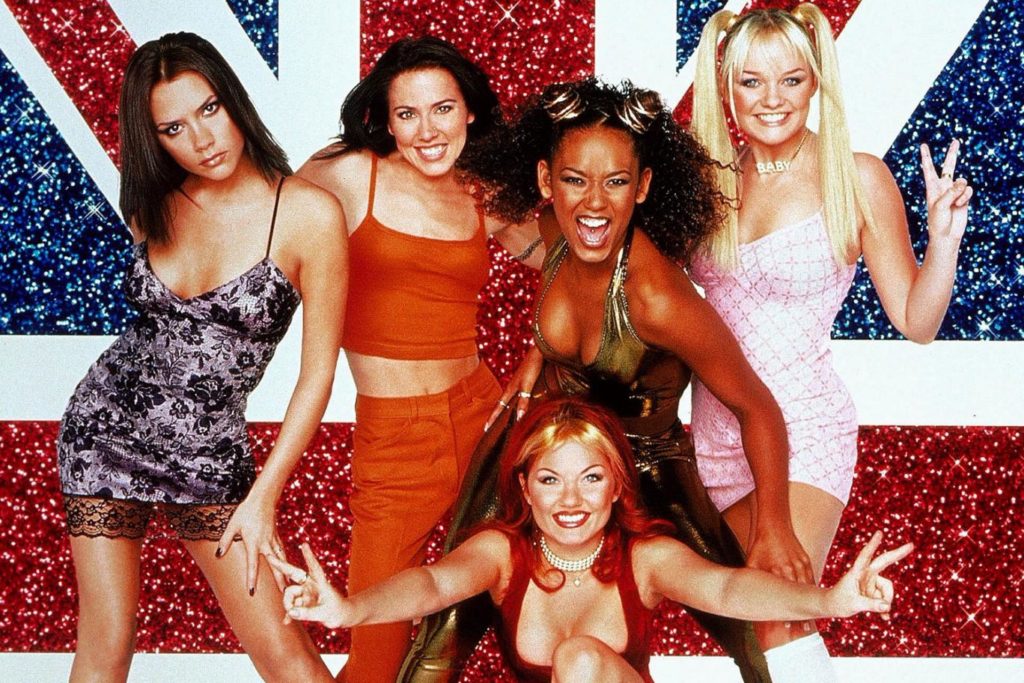

This is all encouraging us to listen up and take heed of the 1990s whenever we go to the cinema. The phenomenon is not, however, confined to the movies. The Spice Girls are back on tour, Tiger Woods is winning golf tournaments again and every other person out there is wearing a leather jacket, dungarees or some unholy mixture of both. It could really be 1997, with Leo and Kate lovingly sailing through the ocean as the refreshing waves of cool Brittania lap at our ankles. From movies to fashion, from TV to sport, we have an obsession with the recent past.

Studios simply seem to get their hit and they run with it. Much has been made of nostalgia in the movies and in society more generally, with affection for the 1980s widely recognised. The ‘90s, however, is a more recent emergence. To establish its exact origins in wider culture is a big ask, but in the realm of cinema, two fairly recent blockbuster stand out that may just have acted as triggers – Toy Story 3 (2010) and Jurassic World (2015). Both made so many deliberate nods to the ‘90s films which preceded them, bringing back old characters and tropes while reintroducing new ones. There is an important difference between the two though. Part of the reason that a fourth adventure for Woody, Buzz and the gang seemed so unthinkable was because Toy Story 3 rounded off their story so perfectly. By contrast, Jurassic World feels less like an ending and more like a second beginning. The finale, in which dinosaurs now rule supreme over an island where at-all-costs capitalism and human hubris attempted to play God, echoes the ending of Jurassic Park (1993) very deliberately. Jurassic World opened the door to a new world of ‘90s nostalgic revival, with an affirmative welcome rather than a tear-jerking goodbye.

If cheap throwbacks are for fools, then a fool’s paradise is not hard to find. Jurassic World raked in a colossal $1.6 billion worldwide and is the sixth highest grossing film in history. The green light for the ‘90s revival was well and truly lit. Since 2015, the 1990s have come flooding back onto the big screen. From Independence Day: Resurgence (2016) to last month’s Aladdin, odes to the decade of Bel Air and AOL have not been hard to find. In Captain Marvel, they are used primarily for humour, whereas the fantastic Beats bases its entire story in a particular piece of the ‘90s jigsaw (namely rave culture). Revivals of films from the 1990s are not going to stop either, with Disney’s latest live action remake The Lion King released later this year, and Mulan (1998) getting the same treatment in 2020. No end is in sight for the ‘90s rebirth.

But surely if you want the future, you have to forget the past? Apparently not. There are many theories floating around about why the 1990s seem to be shaping the immediate cultural future (in the UK and America, at least). Writing in Elle, Robin Givhan speculates that “there was something pessimistic but still naive about the Nineties. The problems that seemed so big and burdensome then, now seem modest. We fretted over the Gulf War; we mourned the death of Princess Diana; we feared the arrival of Y2K. Now, we’d long for those worries and sorrows. Now, the world’s problems aren’t just dark, they’re pitch black.” On top of that, she claims that “the Nineties also gave us a chance to breathe. It was a period of catharsis.” The world was not characterised by naive carefree frolicking nor by solemn contemplation, but a bit of both. Today, with Trump and Brexit, and with the world still recovering from an economic implosion ten years ago, everyone seems more dialled into the sobriety of the present. This is not necessarily a bad thing – and good can (and has) come from this, but it at least partially explains the longing by some to go back.

Everlasting, like the sun, the ‘90s point to some kind of innocent joy in mere existence (a privileged one, for sure) that seems so appealing today. Shannon Mason in the Empire State Tribune writes that “They point to the good feeling that comes with looking back on a simpler time.” In the United States especially – but in the UK too – the 9/11 terror attacks brought in a new storm of gloom and pessimism that killed the anticipation of a new millennium. Mason’s interviewees indicate that this storm hasn’t really gone away, and the ‘90s revival is perhaps an attempt to move past it.

Every boy and every girl could spice up their lives in the 1990s, across popular culture’s many mediums. Both Givhan and Mason were writing about fashion, but a lot of what they conclude is applicable to the movies. Who didn’t at least break out in a small grin when you finally saw the T-Rex in all its glory in Jurassic World? And who wasn’t laughing away when Carol Danvers, Nick Fury and company were waiting tensely for the dial-up internet to kick into action? It’s those film moments that take us back to a particular point in time and right now, it’s to the ‘90s. Because in the current world climate, which can at times disenchant with its hostility and doom mongering, it provides a welcome moment of escape. And what is a good film if not a moment of escape?

The world needs some love like it has never needed love before. The gushing reaction to Toy Story 4 exemplifies the emotional good than can come from it. The 1990s were not great for everyone by any means, and the lasting cultural imagination of the decade undeniably gazes at it through rose-tinted glasses. There was, however, at least enough to celebrate to lay the foundations for such a vision. The movies of the time live on through its biggest stars, most revelatory releases and the continued influence of big names into the next two decades. Put crudely, big names sell and brand power is exactly that – powerful. But the decade’s featuring in the indie scene points to something more profound in our collective memory; a desire to look back, learn and begin again. A time where everything was apparently so much simpler. But as Mason also indicates, holding on to the past like this may prevent us from grasping the future with both hands. Can refreshingly new films, and the most exciting names of 21st century cinema, really reach their potential in such a nostalgia-happy Hollywood? The ‘90s revival is looked at mostly with a wry smile, but it is only ever contingent. One day, Geri will leave the Spice Girls again, and we will all come back to earth with a thud.