The latest film from Sophio Medoidze, a film director and artist who grew up in Georgia, combines the thoughtful and provocative insights of the best documentaries with sweeping, dramatic images of wilderness akin to the most dramatic landscape shots in high fantasy films. Let Us Flow, filmed in an anthropological manner over several years, is a close quarters look at tradition and gender amongst the Tush people in Northeast Georgia. There is both critique and admiration in this intimate portrayal, with people regularly filling the camera shots to make you feel like a member of the crowd, yet they seem to pale in significance to the stunning mountain ranges behind them; a looming reminder of the power that both nature and the past hold.

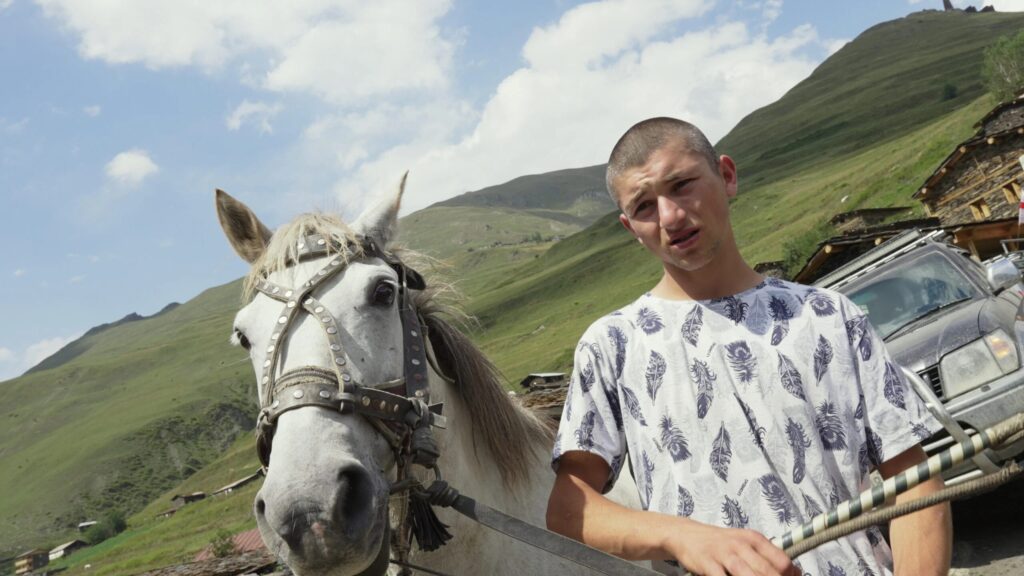

At its core this is a film shining a spotlight on gender divisions, and at the climax of the film this is laid out in a very explicit debate between the men and women concerned. But for Medoidze, this is evidently a deeply personal filmmaking experience, and as a result her depiction is appreciative and nuanced as well as critical. The Tush people make an annual visit to a shrine (access to which is prohibited for women), before the men participate in a dangerous horse race through the stunning scenery – helmet and point-of-view shots wonderfully attest to the exhilarating rush of this yearly hot pursuit.

Medoidze takes great care to show that, while women are not welcome at the shrines, they still sit near the top of the social hierarchy. Their governance is indispensable, and Let Us Flow is as much concerned with highlighting their role while breaking down the showmanship of the men. Medoidze doesn’t make the mistake of using absence to explain absence, instead providing a balanced depiction of how both men and women contribute to a way of life being increasingly influenced by modernity. It is telling that, while cars are clearly used in the village, Let Us Flow only ever shows the Tush people traveling on foot or on horseback. Tradition in the face of change holds serious weight, and Medoidze tasks herself with explaining why.

Let Us Flow’s score and the use of coloured filters for some of the scenes give much of the film a dreamy quality, albeit one that lasts for a fleeting moment before you snap back to reality. At other times contrasting images and scenes play out like a disjointed tapestry, as do a range of different sounds (the calming slumber of nothing quickly flashing to the thundering of hooves down an improvised track). The film’s form catches the contradictions and experience of the people at the centre of Medoidze’s account. Such imagery concerns itself with division down not just lines of gender, but also of the sacred versus the profane and the gap between the physical and spiritual worlds. A respectful, deliberately slow look at how these divisions form part of the Tush way of life is Let Us Flow’s greatest strength. And Medoidze, almost always filming from her perspective yet never stepping in front of the camera herself, uses this as the basis of a hypnotic visual medley.

At just 63 minutes long, you cannot help but feel that far more of Tush life must have been recorded than what has been presented here, and those wishing to know more might just long for an extra slice of raw footage. Nonetheless, what is here is a wonder to behold; a beautifully shot, thoughtfully composed film that celebrates locality and people. Let Us Flow is a transfixing event from Medoidze, still relatively early in her directorial career and someone who clearly has so much to offer.

Let Us Flow received its world festival premiere at the 2023 Berwick Film & Media Arts Festival.