Full disclosure: I walked into the cinema to see This Much I Know To Be True already a fully-fledged Nick Cave zealot. I can’t say precisely when it happened – the point at which my sojourn into the Prince of Darkness’ oeuvre became a permanent stay – but a world without Cave’s music is not one in which I want to live. Despite this, I’m aware that not every reader will be as ardent a Cave-o-phile as I am, and therefore take this chance to assert that Andrew Dominik’s latest film collaboration with Cave and his long-term co-conspirator, Warren Ellis, is so immersive and well-constructed that it’s bound to initiate a host of new Nick Cave converts… A cinematic ‘Rite of Cavean Initiation of Adults’, if you will.

What’s with all the churchy allusions? Well, a vast amount of this sort-of concert film, sort-of music doc’s filming took place in shuttered, vaulted and ecclesiastical looking buildings around Brighton (Cave’s home since the early 2000s) and London. Yet, perhaps more pertinently, Cave’s musical personae evoke a whole array of Christlike allusions (and illusions). With a literary lyricism as rich as that of Dylan and Cohen, Cave’s early song writing drew frequently from the Old Testament and later in his career has borrowed increasingly from the New Testament.

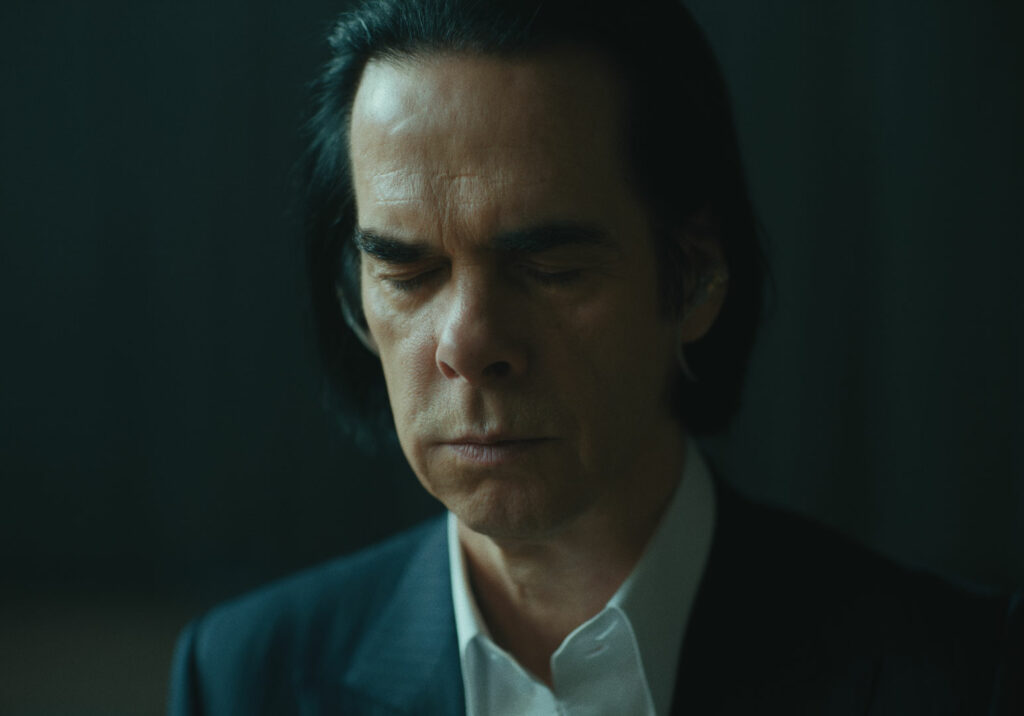

In his typical garb – black suit and white shirt with an almost comically large dagger collar – Cave might bring forth visions of a priestly Elvis officiating a shotgun Vegas wedding. Indeed, in This Much I Know To Be True, Cave is often filmed standing at the mic as in front of some invisible pulpit, arms rising and falling at intervals and palms turned to the heavens as if in prayer, or preaching, or Jesus nailed to a ghostly cross.

Cave’s relationship to theism, however, is seldom uncomplicated and never dogmatic. There is a self-effacing mortal awareness to his act that constantly seeks to undermine attempts at pedestaling him as some messianic force, or coronating him as part of a rock monarchy. Perhaps now more than ever before, in Dominik’s third film collaboration with Cave – following The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007) and 2016 concert film, One More Time With Feeling – Cave is at pains to peel back the veil so often cast over the lives of musicians and artists in the public eye and celebrate the profundity of the mundane.

This Much I Know To Be True begins with Cave declaring that, presumably on the expert advice of Rishi Sunak mid-pandemic, he’d decided to retrain. Alas, in ceramics, not crypto (sorry, Rishi). During this time, Cave created a number of ceramic figures inspired by an origin story of the devil; a character arc moving beyond reductive dualisms of good and evil. Indeed, anyone who has even dipped a toe into the Cave-pool and listened to some of his most widely popular tracks – such as Kylie collab ‘Where the Wild Roses Grow’ or ‘Red Right Hand’ (the theme tune to Peaky Blinders) – will know that his lyrics toy with innocence, transgression, and redemption as narrative motifs. Good and evil; maniacal will and twisted fate weave throughout Cave’s body of work with a flair of a gothic novel, yet without the old dichotomy of earthly, innocent Jane Eyre from wild, angry Bertha in the attic.

Cave’s embrace of all facets of emotional life, including its cobwebbed dungeons, is what earned him his princely epithet, and perhaps it’s also why his listeners feel they can reach out to him for solace in times of hardship. This point is taken up in Dominik’s film, with Cave discussing his ‘Red Hand Files’ project; an online newsletter published by Cave consisting of an ongoing Q&A in which fans sent him often anguished and heartfelt messages. This project of Cave’s was commended in The Guardian as “a shelter from the online storm free of discord and conspiracies, and in harmony with the internet vision of Tim Berners-Lee.” There’s a point here not to be missed: Cave’s music, much like the early internet, enfolds possibilities of communication, reverberation and resonance like electric nodes lit up in the minds of listeners; switching on a sensitivity available to all of us in our mutual humanness.

A common denominator among the different messages Cave reads out on film is how his work – whether with collaborative acts such as early the early Birthday Party years, the Bad Seeds, or Grinderman, or with his solo endeavours – speaks poignantly to human love and suffering and the importance of finding the silver slivers lining otherwise overcast days.

In recent years, since the Bad Seeds’ Skeleton Tree album, recorded in the wake of his son Arthur’s tragic death, Cave’s music has taken on a less jaggedly jaunty, more ethereal and ambient quality. This Much I Know To Be True focuses on Cave and Ellis’ most recent musical ventures with albums Ghosteen and Carnage, shot before their tour last year. The film has many of the properties of the average concert film: punchy performances cut with paired-down narrative moments with Cave and Ellis interacting in the studio and speaking directly to camera. Yet unlike the average concert film, there’s no audience to be found in the chapel-esque buildings which constitute the film’s principal locations.

That is not to say that the performances captured by Dominik and cinematographer Robbie Ryan are without a certain virtuosity… Cave still cuts a striking silhouette amongst the cyclone squall of cameras on dolly tracks encircling the performers – consisting of Cave, Ellis and supporting musicians, as well as rich-timbred vocalists who provide gospel-esque swell of voices around Cave’s Galleon Ship, slicing through the gloom of a performance space which shuns natural light.

Dominik and the rest of the production team clearly recognise the importance of lyrical imagery in Cave’s music, with choice lighting and camerawork often adopting a narrative quality. Marianne Faithfull’s cameo is a great example of this – though clearly struggling and between puffs of oxygen from a ventilator, Faithfull reads writer May Sarton’s poem ‘Prayer Before Work’:

Out of the absolute

Abstracted grief, comfortless, mute,

Sound the clear note,

Pure, piercing as the flute:

Give it precision.

Austere, great one,

By whose grace the unalterable song

May still be wrested from

The corrupt lung:

Give it strict form.

Faithfull’s corrupt lung, ringing out against the austere bareness of the performance space and stark lighting, is looped by Ellis’ recording devices and fades into a backing track for Cave’s haunting rendition of “Galleon Ship”. The lighting transforms from a green-tinged semi-darkness to a bright orange, winking glow; a lighthouse for Cave’s ship in the night. The slow flashing of the lights mirrors the ebb and flow of the vocalists’ abstract wails. Cave’s solemn baritone sing-speaks more poetry:

And if we rise my love

Before the daylight comes

A thousand galleon ships will sail

Ghostly around the morning sun

The frequent interchange between extreme wide angle pans and jump cuts to super tight close-ups of instruments being masterfully played is a themed carried throughout Dominik’s film. As viewers we are never really allowed to settle on one narrative perspective for too long, or become too comfortable.

The following scene is a memorable one; we follow Ellis down a residential street, through a front door and into a house. It looks worse for wear – “I kind of left about a week ago and there’s just shit everywhere, like MTV had a party”…

Ellis leaves through a rare text by Emily Dickinson – Herbarium – before turning to his laptop. From behind the camera, we hear one of the crew exclaim “holy fucking shit! Look at his Desktop Robbie!” Ellis’s desktop is littered with thousands of files; a digital heap of disordered memory. This is congruent with Ellis’ own statement about himself – “I don’t really have a sense of order, that can come later”. Cave touches on the same topic later in the scene when describing the difficulties he and Ellis had whilst working together: “It’s almost pointless writing down a song and taking it into the studio unless I physically hold Warren down and tell him ‘THIS IS A SONG I HAVE WRITTEN AND WE ARE GOING TO PERFORM’.” His tone is jovial but it’s clear the sublime fusion of their musical styles was a hard time coming.

Another comment gives insight into the growing influence Ellis has had over Cave’s music since the Bad Seed days – back then “he took a subordinate role. Then slowly took out each of the Bad Seeds one by one, I’m the next to go.”

Near This Much I Know To Be True ‘s close, daylight seeps through the previously covered windows of the hall. Cave and Ellis perform Kingdom in the Sky. An immense crescendo builds as an ecstatic group climax of song erupts through the hall. The strobe flickers so fast it seems almost as if we’re watching a stop-motion animation. Ellis, who for much of the film has appeared as a bearded wizard, evoking several Jungian archetypes — magician, sage and jester not least — gesticulates with masterful prowess. The backing vocalists are given moments to shine. Cave leads with unwavering conviction.

In one of the final scenes, we follow Cave into a cramped taxi: “I’m much happier now than I used to be. That’s not to say I don’t struggle… It’s not about happiness to me. It about being connected to the meaning of things… The very nature of the world is meaningful… and people are meaningful beings.”

If anything, this is the gospel Cave preaches now. And, whilst I might be biased, it’s definitely one worth hearing.

This Much I Know To Be True is out now in select cinemas, and releases to MUBI on July 8th.