A couple of years ago, centibillionaire Elon Musk appeared on The Joe Rogan Experience and got onto the subject of the rapidly increasing sophistication of video games. “If you assume any rate of improvement at all,” Musk claimed, leaving dramatic pauses and barely supressing a smarter-than-you smirk, “then games will [one day] be indistinguishable from reality. Or civilisation will end. One of those two things will occur. Therefore, we are most likely in a simulation.”

This is one variation on the simulation hypothesis, the proposal – popularised by a 2003 paper by philosopher Nick Bostrom – that our reality could be some form of artificial simulation. It’s essentially a sceptical scenario in the same vein as Descartes’ “evil demon” or the “brain in a vat” thought experiments; equally as fun to think about, and just as philosophically contested. (I’ll be transparent: I think Musk’s specific articulation of this position using the example of video games is ridiculous.)

You can imagine why simulation theory might appeal to someone like Musk: if all reality is a game being controlled by some higher power – though without any of the moral guidance offered by organised religion – why not embark on adventures like colonising Mars, rather than using your vast wealth to actually improve the material conditions of those of us trying to get by on Earth? And you can also see why it would appeal to the kind of Reddit-dwelling folk who view Musk as a prophet: it’s a conspiracy theory masquerading as a respectable philosophical problem that both massages a sense of superiority and justifies a radical solipsism.

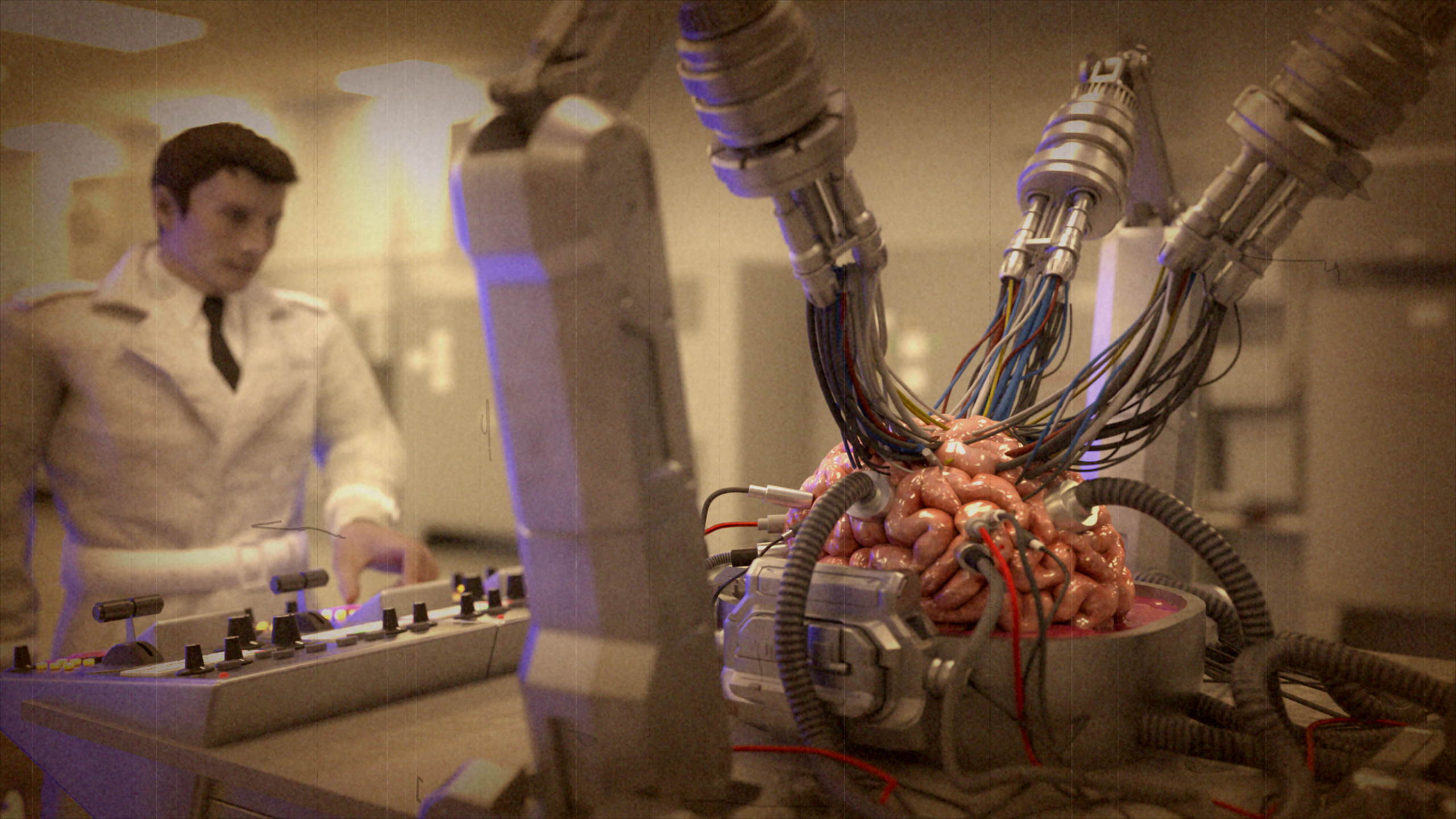

There’s clearly a tonne of potential for a documentary on the recent popularisation of simulation theory. So it’s disappointing – and, to be honest, a little embarrassing – that A Glitch in the Matrix is little more than a platform for a bunch of Elon Musk reply guys to ramble about their personal understanding of the simulation. Director Rodney Ascher takes as his main subjects four true believers whose recorded interviews have been, in one the film’s many empty gestures towards virtuality, overlaid with CG avatars: Jesse Orion appears as an alien in a space suit, Paul Gude as a Roman centurion with a lion’s head, Brother Læo Mystwood as a robotic Anubis in a tuxedo, and Alex LeVine as a brain floating in a bucket-like helmet.

Each of the men explain how they came to understand they were living in a simulation: coincidences started to make more sense as divine cyber-miracles, bizarre events were actually “glitches in the matrix” that exposed the artificiality of our world. As the Matrix reference suggests, the analogies the men draw to support this position repeatedly revolve around video games and movies. Gude thinks of his life as a Truman Show-esque conspiracy constructed like a film set. At one point Orion rants about EA’s video games being overpriced and bug-riddled, and then relates this to our own inadequate world – the simulation we live in, he thinks, isn’t particularly well designed.

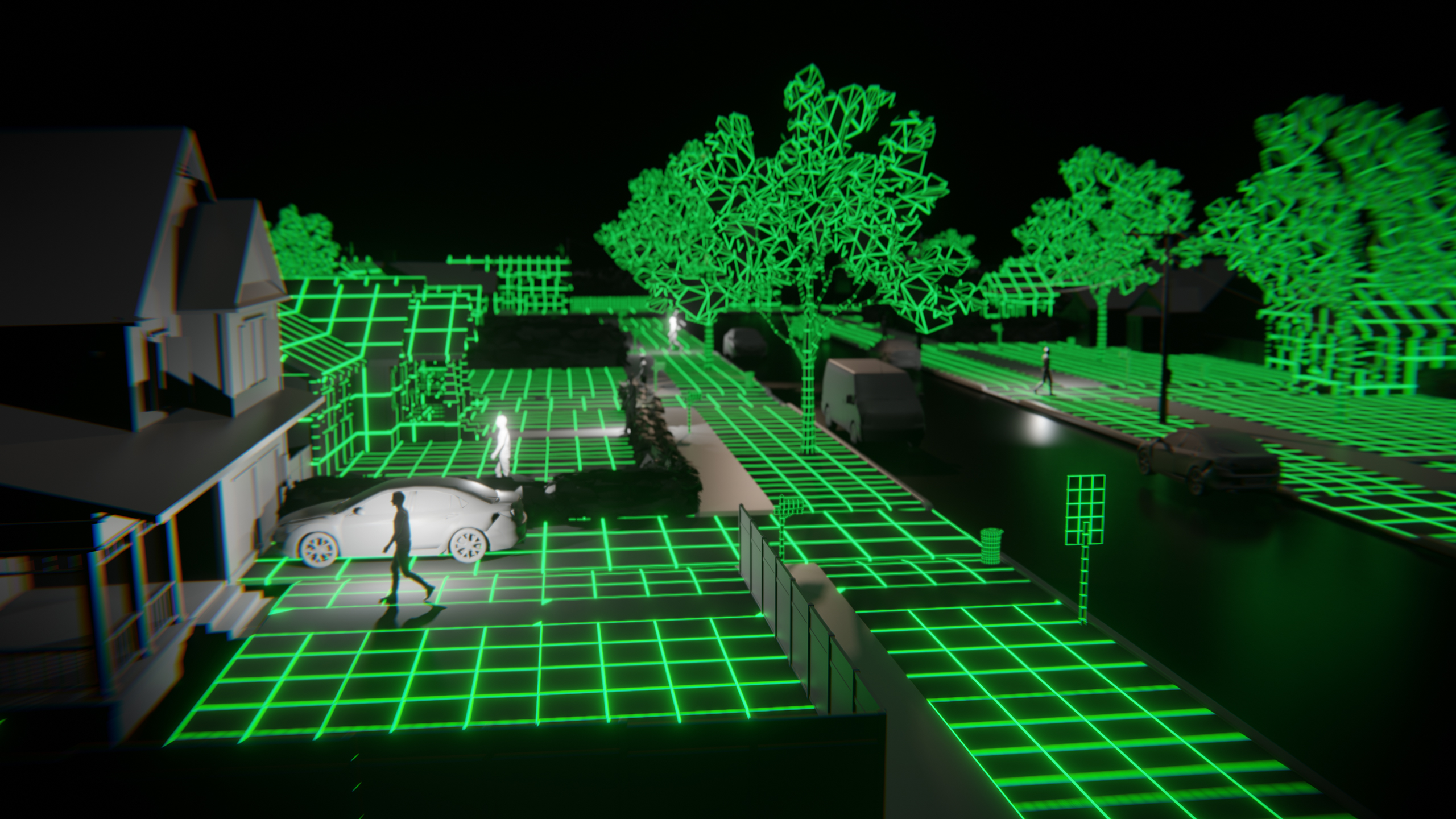

In theory, this sounds like an interesting opportunity to demonstrate the ways in which we increasingly fail to experience ‘reality’ in our media-obsessed world. In practice, Ascher’s method of letting his subjects witter on with almost no pushback is completely tedious. One scene sees Orion providing a lengthy description of how he envisions the exterior of the simulation: as a white marble hall with a giant black sphere at its centre. A sleek animated visualisation accompanied by a moody electronic score grants the monologue a level of seriousness – but the film fails to justify why we should be listening to this arbitrary nonsense over any other.

It’s not exactly that the documentary itself is suggesting that we live in a simulation. But Ascher does seem to want to build his own vague conspiracy through montage. The film is structured around a 1977 lecture by renowned sci-fi writer Philip K Dick discussing the “recovered memories” that convinced him we live in a computer-programmed reality. Between these snippets, and alongside original animation, Ascher bombards the viewer with clips taken from other media, ranging from Minecraft to The Wizard of Oz, to Elon Musk’s Joe Rogan appearance, to a Tana Mongeau video about the Mandela Effect, to – you guessed it – Rick and Morty.

To its credit, the film doesn’t avoid the potentially darker side to one’s belief in the simulation. The subjects, again borrowing from video game terminology, suggest that some people in our world could be NPCs (“non-player characters”) who simply cease to exist outside of our interactions with them. The reason we find ourselves marvelling that it is a “small world”, LeVine claims, is because “it is actually – there just isn’t enough processing power to render seven billion consciousnesses.”

The endpoint of simulation theory as a chilling excuse for the dehumanisation of others is brought to light when the documentary shifts its focus to the case of Joshua Cooke, who at 19 years of age killed his parents after his obsession with The Matrix convinced him he was trapped in a simulated world. The story itself, told through phone interviews with Cooke, is horrific, particularly in his account of the moment he realised that real life violence was nothing like the movies.

If this case study is meant to pivot the film from a light-hearted indulgence in a whacky theory to a moralistic telling-off, it’s undermined by Ascher’s sensationalism. Cooke’s presence is teased out as if he’s a villain in a crime thriller, and the scene in which he describes the murders in gruesome detail are animated and edited like a horror movie. The documentary is ultimately guilty of the very crime it accuses its subjects of – failing to distinguish reality from its simulation.

A Glitch in the Matrix is out now.