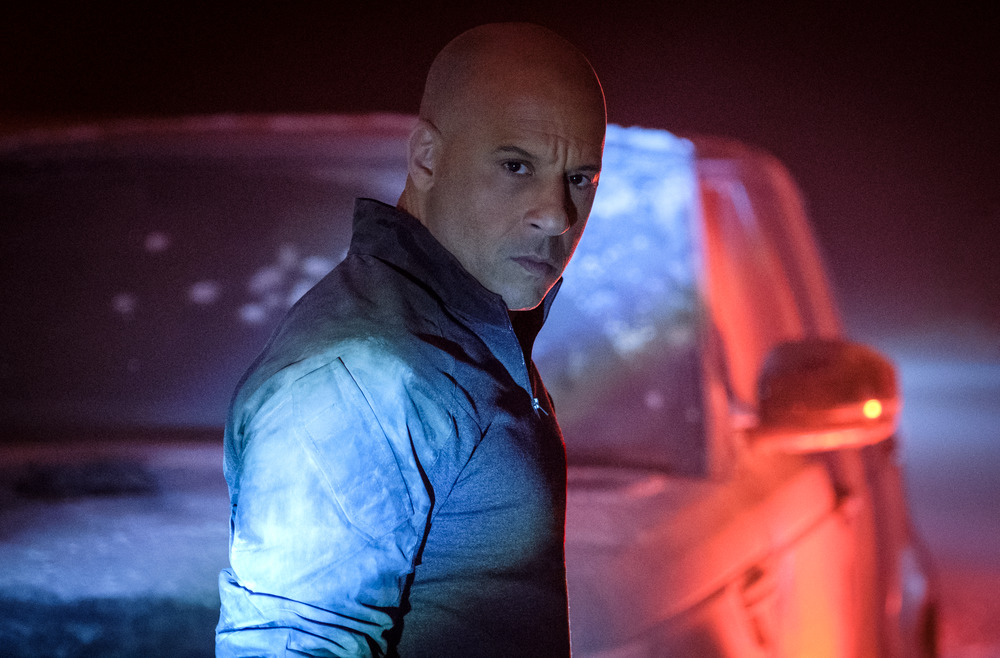

Bloodshot is a cyberpunk-tinged superhero action movie starring Vin Diesel, with a supporting cast including two women, Talulah Riley and Eiza González, only one of whom is quickly fridged to instigate a revenge plot. This is progress, people!

Just to get everyone up to speed, Vin Diesel is (of course) an impossibly macho Navy SEAL, who is murdered by a psycho-killer mobster shortly after witnessing his wife being dispatched with a cattle-bolt (“Can she take all 6 inches? Why am I asking you that?” is just one example of the tonally-bizarre crassness to which Bloodshot falls victim). Luckily, Diesel is resurrected by a mega-corporation’s super-nanotechnology, giving him a second chance to track down and slay his wife’s murderer. Except as we soon find out, and as everyone who’s seen the trailer knows, the megacorp’s CEO has been bringing Vin Diesel back repeatedly, each time programming him with a new set of false memories to persuade him to kill those scientists privy to the secret of nanobot resurrection.

Bloodshot’s gimmick does, however, grant the film a narrative blank cheque. What appear to be plot holes early on, blatant contrivances to get us to the action faster, are soon revealed to be a part of Pierce’s manipulations. Overused tropes of the action-revenge plot are therefore deliberately salacious and over-the-top inventions intended to motivate Vin Diesel’s kill spree. Similarly, Vin Diesel’s wife who gets ‘fridged’ at the beginning is later allowed to have a real identity and life separate to the widower-revenge plot the film initially pretends to be built on. It’s uncertain whether this lampshading actually lets the film get away with it.

Bloodshot is essentially a very good action movie and a spectacularly-executed power-fantasy, with a topsoil of cyberpunk. It’s exciting stuff, and the CGI for the nanobot Wolverine-like healing powers is gruesome, and awesome. However, the focus on visuals and awe-inspiring action undermines the value of the cyberpunk genre: its philosophical reflections on the advancements of technology and science in relation to humanity.

Its hard-sci-fi premise implicitly poses traditional cyberpunk questions – Where is identity located in the cyborg? Can we trust the memories of a cyborg brain? What will be the state of employers’ control over employees in a high-tech future? – but “implicit”, as opposed to explicit, is the key word. Bloodshot is Robocop (but less overtly political) meets the looping shenanigans of Source Code or Edge of Tomorrow, with aesthetic shades of Ghost in the Shell and Alita: Battle Angel.

Those hard-sci-fi/cyperpunk elements are both over-explained and under-developed. It’s spelled out in several ways how the memory/emotional manipulation works, up to and including Guy Pierce (an excellent evil CEO poorly served by some of the writing) just flat-out using the word ‘manipulation’ in an offhand rant to Eric, the cyperpunk nanobot-programming intern.

On the other hand, the political critique is subpar compared to the titans of cyberpunk, such as the recent political-philosophical masterpiece that is Netflix’s Altered Carbon. For example, in a couple of scenes Pierce threatens González with switching off her high-tech respirator which she needs to breathe (and yes, breathing is the female character’s superpower) to coerce his mercenary ‘employee’ to do his bidding. It’s a visceral metaphor for how capitalist society uses the threat of starvation and homelessness to coerce people into surrendering their labour. But that very directness, that lack of any ambiguity actually works to detach the narrative from its real-world parallels, undercutting its critique of capitalism.

Bloodshot is out in cinemas now.