Maɬni – Towards the Ocean, Towards the Shore (Maɬni is pronounced Moth-nee) is the first feature-length film from the acclaimed short film director Sky Hopinka. It focuses on the Chinuk Origin of Death myth, which questions and affirms the place of the Chinookan people’s place on earth and within the cosmos. The film follows two individuals, Jordan Mercier and Sweetwater Sahme, as they share details of their lives and explore how they situate themselves within this myth and in relation to their indigenous identities. Outtake sat down with Hopinka to discuss the production of the film, its significance, and how it fits within his broader focus on native culture and folklore.

I first watched the film when it was part of the Berwick Film and Media Arts festival back in September. I get the impression that you’ve been involved with the festival for a few years?

Sky Hopinka: Yeah, I had a short film shown there and I was a guest juror a few years ago. Last September was the first international screening I had. Before that it was in Canada in April, and then the US in June, January and then March. But BFMAF is definitely a festival that I really wish that I could have attended in person. I had such a good experience there in the past.

What did the process of making the film look like? How did you approach it, and how long did it take to put together?

Sky Hopinka: The film really began with, for one thing, a desire to make a feature length film and see how my short filmmaking practice can scale up into something longer. Once I started thinking about that, the first idea that came to mind was the Chinuk Origin of Death myth, which I’ve been thinking about for a number of years since I first started learning Chinuk Wawa. It reflects my interest in reincarnation and cosmological travel, like belief systems. One of the first films that I had made [Fainting Spells] was about Chinuk Wawa, and it features Jordan Mercier. We’re both acting in it and we’re both speaking Chinuk. We always wanted to return to that world that we made with that little short film, and all of those different ideas seem to align; a feature length film, the Origin of Death myth, involving Jordan, and featuring Chinuk Wawa.

From there, it was about trying to develop a strategy with locations based around where to shoot and what to shoot. I think all in all, the process took about two or three years. When I began editing and putting together assemblages, there was still probably another year of shooting after that where I would put together an assemblage, see what I needed, and go shoot some more. Then I kind of went back and forth on that process until probably the very end.

Why is this a story that you wanted to tell? Why is it important?

Sky Hopinka: A big part of the reason why I make films is to try and tell stories, or try to look at different aspects of indigenous culture and life that aren’t often highlighted or platformed through more mainstream modes of representation of indigenous peoples, in the United States specifically and in Canada as well. Maɬni is a further exploration of some interests that I’ve had which I haven’t seen talked about much before, but it’s also something very personal to me. So really it just became like, ‘Why not?’ This is of interest to me, my friends, and to the people around me who are supporting the creation of this project. Really I’m making a film for a conversation to be had within the community itself.

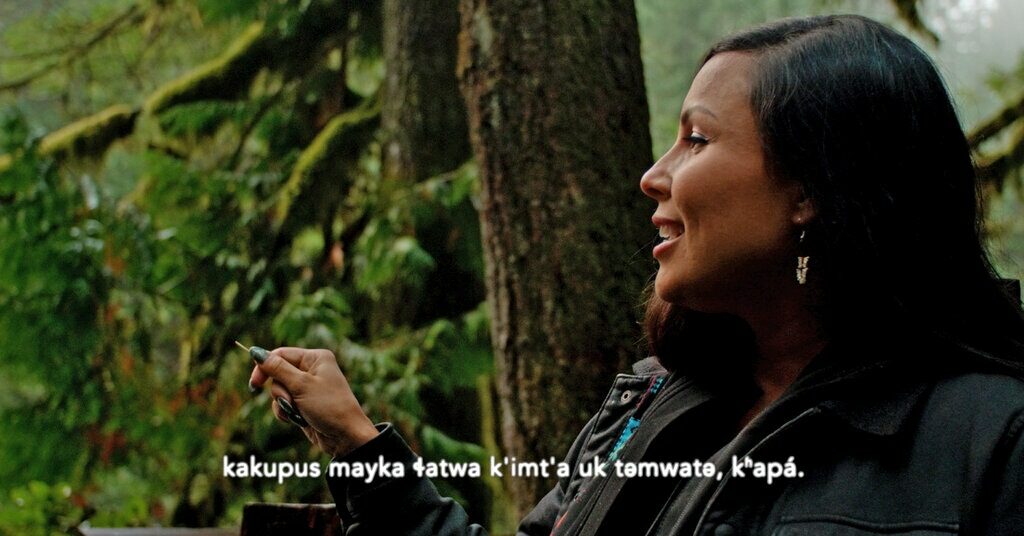

Language plays such a massive role throughout the film. One of the most striking details was that both the Chinuk and English dialogue were subtitled. How would you describe the importance of language in the film, and did it present any unique challenges when you were trying to make it?

Sky Hopinka: It’s pretty central. I’ve done a lot of work with language, subtitles, and translation with a lot of my short films, and this was a film that I knew I wanted to be in Chinuk Wawa. With Jordan being a speaker, and me being a speaker, that was part of the process for the film to be entirely in Chinuk. But then Sweetwater came on board early on in the process, just as I was doing some test shoots. She doesn’t speak Chinuk, and so there was a question about how we deal with Sweetwater not speaking Chinuk in the film. Do we translate what she says? Does she write a script? Does she learn Chinuk? The simplest solution also turned out to be the best one, because it offered a way of dismantling certain hierarchies surrounding language or language learning.

My first language is English, and I felt a lot of shame growing up because I couldn’t speak my heritage language. I didn’t speak Ho-Chunk or Pechanga. I’ve noticed that there is a lot of shame around language learning, and around the fact that we don’t know the languages, and I don’t think that’s a healthy emotion to have towards learning language. I don’t want people to feel ashamed about who they are. And so this became a way of trying to flatten those hierarchies a little bit. I mean, I offer no solutions and I don’t even know if I have any solutions to offer. But with an equal treatment of Sweetwater and Jordan as they speak the language in a way that, in some regards, is just flat, that was a way to offer the audience an understanding of both languages in non-hierarchical terms; not in a way that paints one as being better than the other, which isn’t the conversation that I’m interested in.

How well did you know Jordan and Sweetwater beforehand? You mentioned that you have worked with Jordan in the past. Have you worked with Sweetwater as well?

Sky Hopinka: A little bit. I’ve known Sweetwater since 2006, and I’ve known Jordan since 2010. Sweetwater did appear in another short film that I made around Chinuk and Portland, Oregon called Anti-Objects. We were just hanging around, I was shooting and she ended up in some frames. And that’s kind of what happened with this project too.

The friendships that we have are pretty key to the film or even just how comfortable I am around people, and also how comfortable they are around me, emphasising that level of respect through documentary practice.

How important was it for you and for them to not just speak with them in a darkened room for example, but to actually go out there to the places and to the people that they were talking about?

Sky Hopinka: It was very important. Going to these different locations got us out of that ‘dark room.’ It got us out of that ‘talking head’ framework. Really it was just Jordan and Sweetwater taking me to places that they wanted to show me. With Jordan, we went around the reservation a bit and shot some things in the forest. We also wanted to go on a canoe journey, which is a huge tribal affair in the Northwest. With Sweetwater, she was taking me to her favourite waterfalls and her favourite places to go hiking, to walk around and to be in nature. That all felt very much part of the conversation too, where they have a say in where they feel comfortable, but then also what they want to show me, what do they want to show the camera, and potentially show an audience.

So they very much guided the narrative and the journey? You didn’t have a set idea of where you wanted to go beforehand?

Sky Hopinka: I knew I wanted the ocean, the mountains, the forests, and the river… yeah, from the mountains to the sea. I would play with the title and the idea of these boundaries, and then have Jordan and Sweetwater fill in the blanks. They guided me to wherever they wanted to take me.

Can you elaborate slightly on the boundaries that you mention? How did they come to influence the way that you approached the film?

Sky Hopinka: From the outset, the idea of the boundary between the living and the dead, between the spirit world and the world of the living, was one of the tensions that I felt really drawn to. Especially in trying to construct it or even as I was editing it. The myth is about the boundary of life and death. The agreement on the boundary, as well as the idea of natural boundaries and whether there are any natural boundaries, and are all these choices that we’re living with repercussions of that initial choice… that was something that I wanted to focus on as well. When I started making the film, I didn’t want to make a film about the myth, but about the repercussions of the myth and how these two people exist in this world, living through these repercussions. Which is far more interesting to me than just recreating the story, and it also just didn’t feel appropriate to do from a cultural context.

I guess, more broadly speaking, with indigenous culture – which is often the subject of my films – I’m not interested in just pointing out the thing I want to talk about. I want to actually talk around it, to help give it further shape. To help further define and give boundaries to what this idea is that otherwise may be indescribable or hard to find words for.

What has the reception been to the film so far? What kind of comments have you received from people who have watched it?

Sky Hopinka: I’ve generally heard positive comments and feedback… I don’t think anyone has told me anything negative to my face, but you know it’s the way it goes! When people talk to me about the film, it’s always gratifying to hear them describe it in a way that I feel like I can’t or that I couldn’t put into words. I’ve heard a lot of different feedback from native people and non-native people, from people that live across different communities, and the responses have generated a lot of conversation which has been great. Jordan and Sweetwater were both really happy with the finished film, too.

Let’s talk about your plans going forward. Do you see Maɬni getting a wider release? Are you already working on another project?

Sky Hopinka: I think [in the short term] just continue to try and support the release of the film. I am going to be working on a new project, a new feature length film based around Pow Wows and Pow Wow culture. So it’ll be more of a documentary as well. How it will take shape, and whether it will lean in a more experimental direction, I’m not sure yet. But it probably will, and I’m hoping to start shooting that in the summer of 2022. Between now and then I’m working on a short film and an installation, so just trying to keep busy!

You can also read our full review of Maɬni – Towards the Ocean, Towards the Shore.