Castle in the Sky is the film that solidified now-legendary filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki’s vision and became the model against which future Ghibli films would identify themselves; no other feature embodies Miyazaki’s directorial style, politics, and passions as completely as this 1986 work. It has become something of an underrated gem – though loved by many, it is often eclipsed amidst the Ghibli portfolio by the likes of Spirited Away, Princess Mononoke or My Neighbour Totoro, but Castle in the Sky nonetheless remains the most important of all of Miyazaki’s works when it came to defining his career trajectory.

It is well known that Miyazaki is the key director at Studio Ghibli. Founded in 1985 by himself, his fellow filmmaker Isao Takahata, and producer Toshio Suzuki, their first adventure as a studio was Miyazaki’s Castle in the Sky, an exhilarating adventure about a two young people on the hunt for a floating island. Impressively, this was only the director’s third feature film, following Lupin III: Castle of Cagliostro and Nausicaa: Valley of the Wind, and the first to be released under the Studio Ghibli banner.

Our adventure opens with roaring engines, a gang of air pirates, guns blazing, and a young girl bravely escaping her captors by scaling the side of a giant air ship – and this is all before the title sequence even flashes on screen. Arguably one of Miyazaki’s most exciting and jam-packed openings, it already identifies this film as a true adventure; and yet, what certifies this Tintin-style animation as a Ghibli happens in the moment when the girl slips and soars through the navy night sky, plummeting towards the ground only to be saved by the mystical, glowing crystal around her neck. Long-time Ghibli composer Joe Hisaishi’s swirling strings comes in and suddenly, the audience is witnessing awe-inspiring magic.

Sheeta, the girl from the sky, finds herself having fallen into the heart of a small mining community and saved by Pazu, a young and enthusiastic worker. Though the majority of the narrative takes place up in the sky, the mining community is situated as the heart of the film. Miyazaki visited Wales in 1984, in the midst of the miners’ strikes, and was so deeply affected by what he witnessed that he returned two years later to carry out research for Castle in the Sky. “Many people of my generation see the miners as a symbol; a dying breed of fighting men. Now they are gone,” Miyazaki told the Guardian in 2005. It is clear in how he infuses the industry with beauty that Miyazaki sees the mining community as noble: the gentle fog in the morning, to the chirping birds that wake up the town to Pazu’s trumpet call. The town is perfectly situated within the hills, harmonious with nature – a Utopia for the ever ecologically-minded Miyazaki, who has been no stranger to criticising our modern society’s willingness to destroy the natural world for the sake of corporate conglomerates.

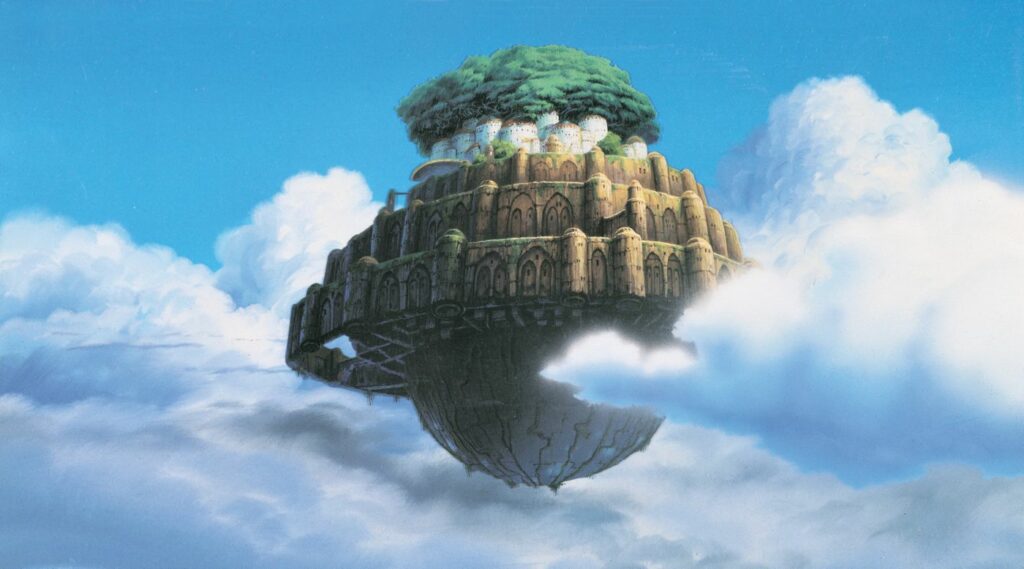

Here, mining is shown to be a different kind of industry, with steampunk mechanics and a lack of smog or destruction; an antidote to mass production with a romantic vision of the humble, blue-collared town of quirky characters full of heart. There is a folkloric element to the design and the narrative, foreshadowing a key feature of Miyazaki’s career: the inclusion of mythology and legends are often deployed to add depth to the worldbuilding in his films. In Castle in the Sky, Laputa is a floating, mythical island which Pazu and Sheeta are determined to find. Miyazaki also takes inspiration from literature, finding inspiration for his first Ghibli in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. Adapting and taking inspiration from European literature and settings is something Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli continue to do. Much like Howl’s Moving Castle, Kiki’s Delivery Service and Porco Rosso, Castle in the Sky takes place amidst an idyllic European-inspired landscape. The luscious green hills and sunlit cliffsides create a perfect vision of the natural world.

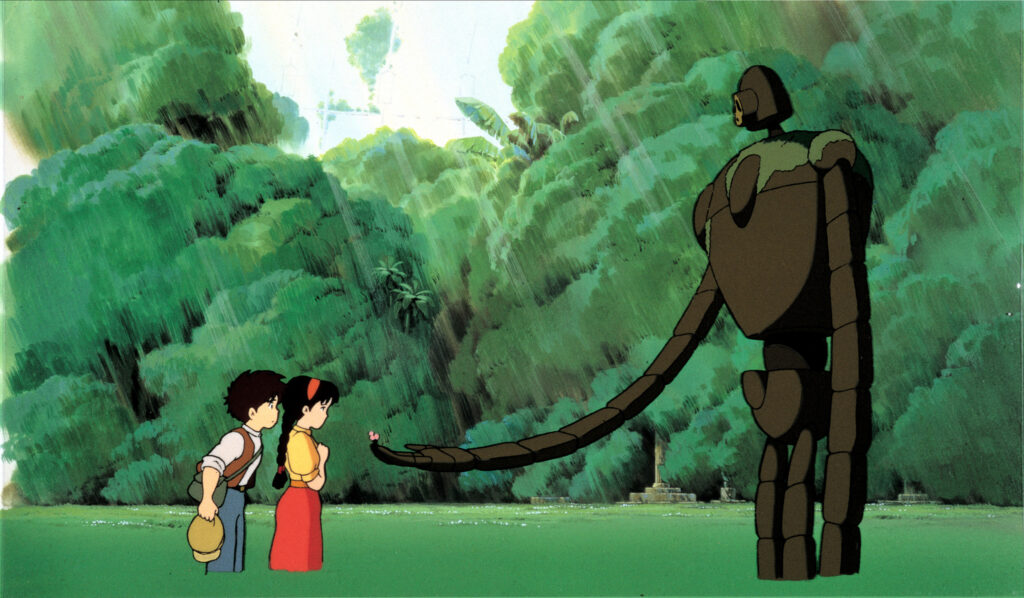

Arguably, what Miyazaki’s diverse body of work is defined by, above all, is his love of nature. This is most exemplified when Pazu and Sheeta arrive through the storm to the island of Laputa, a once towering civilisation of impressive architecture now covered in overgrown vegetation. Nature has fought back, and the natural wildlife now lives in harmony with a Laputian robot. This solitary surviving robot of Laputa, formerly used as a weapon of destruction, is the caretaker of the Island; protecting the eggs of birds, bringing fresh flowers to the memorial, and overall living at one with nature. Relatedly, Miyazaki’s strong anti-military, anti-colonist, and pacifistic politics are also on full display. The army and the government are the antagonists of Castle in the Sky, as we see them seeking out Laputa to take its treasures and harvest its power for selfish, destructive gains, with no regard for the indigenous life. Miyazaki is vocal about his beliefs, famously refusing to accept his Academy Award for Spirited Away in protest of the US’ involvement in Iraq. No film of his exemplifies this pacifism more than Castle in the Sky, epitomised when Sheeta proclaims: “No matter how many weapons you have, no matter how great your technology might be, the world cannot live without love.”

While there is no doubt Castle in the Sky is a little rough around the edge – the animation style was in its early days, and the film lacks some of the meditative qualities of later Ghibli productions –, it still functioned as the perfect springboard for Miyazaki and Ghibli’s following films. Each feature would improve on and build upon the solid bones that Castle in the Sky laid bare. A strong female protagonist, a civilisation overgrown by nature, a host of different airships and flying mechanisms, a mining community and a pacifistic core; one has to wonder if Castle in the Sky might not still be the most quintessentially Miyazaki film that he has ever done.

Castle in the Sky screens as part of the BFI’s Anime Season, which runs from March 28th until May 31st.