Ousmane Sembène’s seminal 1968 film Mandabi received a 4K restoration from Studio Canal, with this work of Senegalese cinema becoming available for the first time in the UK on June 11th. The first movie ever made in the Wolof language and Sembène’s second feature, Mandabi was a major step towards the realisation of his dream: to create cinema by, about, and for Africans.

Fifty-three years later, Mandabi still has much to say about colonial legacies in Senegal.

The past is present

It was July 2017 at the G20 Summit in Hamburg, Germany, when French Prime Minister Emmanuel Macron identified what he believed to be the “civilisational” problems of Africa. Yet many of these “problems” boiled down to grossly racist, totalising stereotypes that felt much akin to the very rhetoric that had justified European invasion and control of the African continent from the 16th to 20th centuries.

When I watched Mandabi (1968), directed by the “father of African cinema” Ousmane Sembène, I could not help but think of Macron’s quote. The logics of neocolonialism demand monolithic, anti-Black command of African land, peoples, and languages. Neocolonialism and white supremacy construct stories of Black “failure” versus white “success” to then rationalise global inequity and present-day colonialism.

In Mandabi, Sembene undermines these white supremacist, neocolonial logics by demonstrating that it is not Senegalese people themselves that maintain situations of “failure” or “civilisational problems”. Rather, Mandabi exposes that the true sources of daily struggle for the average Senegalese citizen are the French colonial systems and mindsets that remain in post-independence Senegalese society.

Money and coloniality

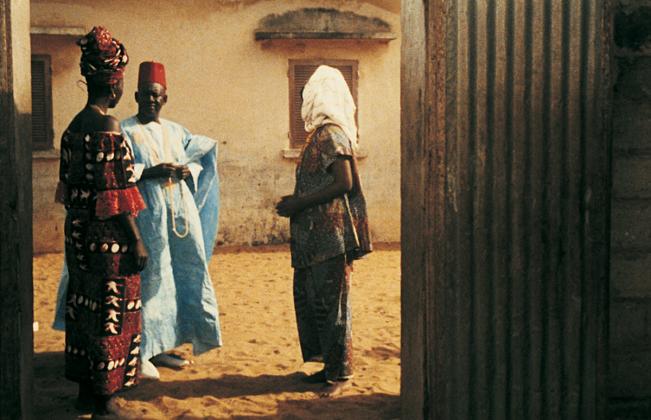

Mandabi follows Ibrahima Dieng – a poor, illiterate man with two wives, Maty and Aram, and their seven children – as he receives a money order from a nephew who has recently immigrated to France to find work. Dieng presents a tragicomic lead: he is labelled a “helpless show-off,” a point made when we see him repeatedly toying with his oversized, over-flashy boubou to make himself appear bigger and more important.

However, we soon learn that Dieng is illiterate and has been unemployed for four years. He and his family have largely lived day-to-day without ever encountering government bureaucracy; thus, when the money order appears, Dieng’s collision with a bureaucratic system is quick to expose how older, illiterate, and unconnected men are easily made prey to systemic colonial violence.

Erased by the system

One of Mandabi’s most notable scenes sees Dieng try to get a hold of his birth certificate, after both the post office and police precinct deem that he cannot cash the money order without proof of ID. He goes to the city hall to obtain his birth certificate, only to be met by disaffected and unkind clerks who refuse to help him. Two younger Senegalese people eventually step up to help Dieng and read him his birth information – but the proof of Dieng’s existence only includes that he was born “around 1900″.

Even shared literacy cannot come to Dieng’s aid when his very existence does not align with arbitrary colonial parameters. Legitimacy (or lack thereof) then plagues Dieng’s various attempts to cash the money order meant to for his nephew Abdou, and Abdou’s mother.

Representations of power

Whiteness and coloniality appear in Mandabi as signifiers of the embeddedness of white supremacist values. Dieng, Maty, and Aram’s children play exclusively with white dolls – dolls with eyes like surveillance cameras. Meanwhile, the scene in which Dieng initially fails to obtain his birth certificate is tempered by a shot of a white family leaving the same city hall, having successfully obtained government documents. When Dieng and others bemoan the state of the Senegalese country as one wrapped in cruelty and failure, the blame for these problems is placed squarely at colonialism’s feet.

Dieng’s wives, Maty and Aram, are undoubtedly Mandabi’s most interesting characters. Their dialogue in scenes in which Dieng is not present reveals the existence of many economies; particularly, it emphasises how differently they, as women and wives, navigate ideas of money and truth. The first to know about the money order, Maty and Aram are initially distressed by the threat of a government presence infringing on their lives, even as that money holds the promise of food and security for their children. They know that however poorly ageing, unconnected men are treated, things are worse for their female counterparts.

Conclusion: Mandabi and today

Mandabi lays bare the realities of “post”-colonial legacies through the many, many trials that Dieng must face to cash the money order. The film’s end, a montage of Dieng’s experiences in gaining and losing the money order, solidifies the suffering that white supremist bureaucracy and colonial ghosts have wreaked upon him and his family.

In her revolutionary text In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (2016), Christina Sharpe argues that the world that we live in today exists in the continuing, ever-present wake of slavery and the imperial systems it manifested. “In the ground we walk on,” these logics of neocolonialism and anti-Blackness pervade every tier of life, from the governmental to the familiar – Mandabi certainly serves to illustrate this.

Mandabi will be released in cinemas June 11th.