David Fincher is one of the last true auteurs: over the last twenty-five years, he has directed and produced a catalogue of instantly recognisable, ruthlessly effective, uncompromisingly bleak morality tales, becoming equally beloved by audiences and critics in the process. It was his second feature film Seven, however – with its game-changing mixture of horror and film noir, pitch-perfect casting and that noggin-bothering final scene – that established him as a serious movie-making talent. Even after twenty-five years, here’s why Seven still slaps.

Before September 1995, the man responsible for modern classics like Zodiac, Fight Club, The Social Network and House of Cards was little known outside of industry circles. Early in his career, David Fincher worked for special effects titans Industrial Light and Magic on Return of the Jedi and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom – among others – before striking out on his own and establishing himself as one of the most talented music video/ TV commercials directors in the business.

Eventually, Fincher made the move to feature films, but his feature debut was such an unmitigated disaster that he almost packed in movies for good. After his calamitous first experience directing Alien³ (or ‘Alien Cubed’ for those in the know), the traumatised young filmmaker famously claimed he’d rather “die of bowel cancer” than direct another studio film. Thankfully for audiences – and for Fincher’s digestive tract – he was eventually convinced to take another stab at movies when the script for Andrew Kevin Walker’s Seven fell into his lap one fateful afternoon.

“People don’t respond to ‘help’; you holler ‘fire!’ and they come runnin’…”

Just like its elusive antagonist, Seven is a masterclass in creating and sustaining an atmosphere of claustrophobia, apathy and dread. The threat of violence and the cold hand of judgement is ever-present but frustratingly elusive and, most importantly, always one step ahead of our plucky heroes. Seven takes place in a cold, unforgiving city where almost every conversation is a confrontation, empathy is rewarded with ridicule and gruesome murders frequently go unsolved and unpunished. As Morgan Freeman’s Detective Somerset wearily puts it: “We gather evidence, file it away… Collecting diamonds on a deserted island, stowing them away in case we get rescued.” The camera is purposefully slow and methodical, keeping a cool, detached eye on Detectives Mills (Brad Pitt) and Somerset as they scramble to keep up with the murders, and the audience is invited to view this grim spectacle with the same voyeuristic, curious eyes as the ever- present John Doe.

The dramatic, brassy soundtrack, cool grey colour palette, subtle focus on classical and art deco architecture and use of outdated technology all work in tandem to create a timeless noir feel, suggesting the eternal, unchanging nature of the struggle for law and order. These stylistic touches contrast with the shocking, fantastical elements of the gory crime scenes and imbue the city with an Old Testament level of grandeur, lending a tyrannical, authoritarian quality to even the homeliest of spaces. Additionally, the city remains forever nameless – visually recalling both New York and Los Angeles – and the murders are committed throughout every level of society, suggesting an epidemic of crime and deterioration from which no-one is safe.

The entire aesthetic, from its chaotic, invasive sound design where arguments bleed through walls and phones interrupt important speeches, to the muted colour scheme, nauseating murder scenes (featuring live cockroaches!) and constant, torrential rain, presents the city as though it were the contents of a petri dish: equal parts fascinating and repulsive, under siege by unknown forces and thoroughly infested.

“Independently wealthy, well-educated and totally insane.”

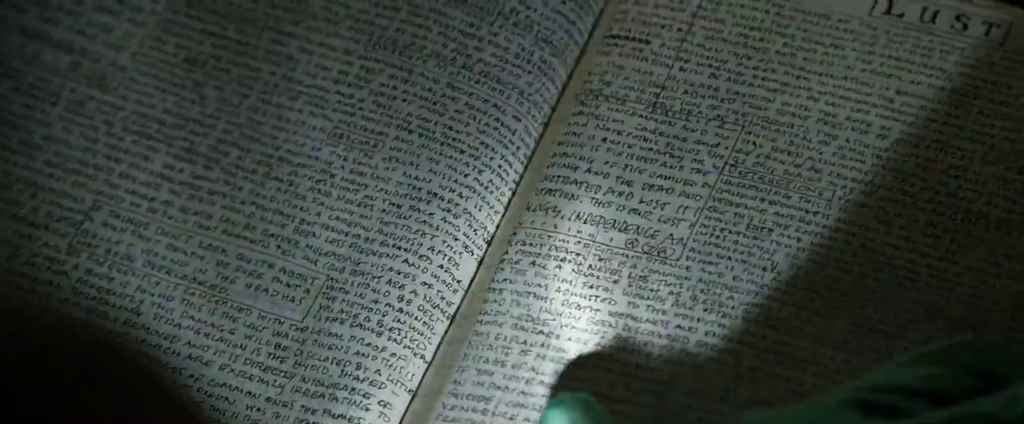

In order to further establish the character of John Doe whilst preserving that all-important sense of mystery (Kevin Spacey’s name was omitted from all promotional material to preserve the surprise), Fincher enlisted the talents of Production Designer Arthur Max, artists Clive Percy and John Sable and photographer Melodie McDaniel. They ended up producing an extensive collection of photographs and over 25 individual, frighteningly detailed notebooks documenting Doe’s unhinged inner thoughts and rantings. Sable personally produced hundreds of pages of “incredibly perverse, stream-of-consciousness, anal handwriting” in order to portray Doe’s obsessive, irrational anger at the world, and included grotesque crime scene photographs that ended up terrifying the employees at a local photocopying outlet.

Similarly, Melodie McDaniel used cheap cameras, out- of focus shots, scratches on the lens, over- and under-saturation and other techniques to create the amateurish feel that adds a manic dimension to the otherwise calm and collected killer’s personality. Even though they are only glimpsed on screen briefly – scattered around Doe’s apartment and various crime scenes – the attention to detail and sheer volume of this serial-killer detritus gradually builds one of the most fully-formed, in-depth depictions of violent psychopathy ever put to film.

“I’ll be around.”

As Detective Somerset, Morgan Freeman provides the moral centre of the story; a man on the edge of retirement who is almost consumed by apathy and regret but nonetheless remains a thoughtful, empathetic presence throughout. Mills, on the other hand, is a brash, crass, inexperienced but talented rookie eager to prove himself in the big city, dragging his newly pregnant wife Tracey (Gwyneth Paltrow) along for the ride. The trio of Somerset, Mills and Doe make for a superbly constructed finale in which the balance of power is flipped back and forth, as our two protagonists are forced to reconcile their own definitions of morality and justice in what has to be the most high-stakes game of ‘Deal or No Deal?’ in history. Few films since Seven have even dared to attempt to match its notorious final reveal, and even fewer have succeeded.

As soon as Somerset discovers “What’s in the box?”, the audience knows that Doe has the upper hand. After Doe’s final, devastating confession, Mills briefly struggles with his baser desires before killing the villain, becoming wrath: an unwilling accomplice and the final piece in Doe’s macabre master plan. In the appropriately pessimistic words of Fincher: “The double-edged sword of the movie is that you give the vengeance-crazed audience their blood-lust – what they come to movies for – but at the same time… these are the circumstances under which this choice is being made… and there aren’t enough bullets, you can’t do enough damage to him, for it ever to be even.”

It is a masterfully bleak coup de grâce that both Pitt and Freeman fought with studio heads to keep in the film; one that fully delivers on the nihilistic promise of the previous 90 minutes while still leaving room for a tiny speck of hope. In the end it is the dignified, philosophical Somerset who emerges, and achieves a victory of sorts over John Doe, as he eventually decides against retirement, resolving to keep fighting despite all the depravity he has witnessed and overcoming the apathy that initially plagued him.

It’s true that Seven didn’t inspire a slew of copycat films like The Sixth Sense or The Matrix, but this fact only attests to its success and enduring, singular place in the pop-culture pantheon. It borrows from horror movies, police procedurals and noir thrillers, but defiantly resists classification. With Seven, David Fincher blessed the world with one of mainstream cinema’s most shocking twists which, like the image of a gigantic alpha walrus wearing a bladed, eight-inch marital aid, plagues the mind and lingers for days: a terrifying, head-spinning creation that utterly bowls over all challengers. To paraphrase: “They’ll barely be able to comprehend it. But they won’t be able to deny…”