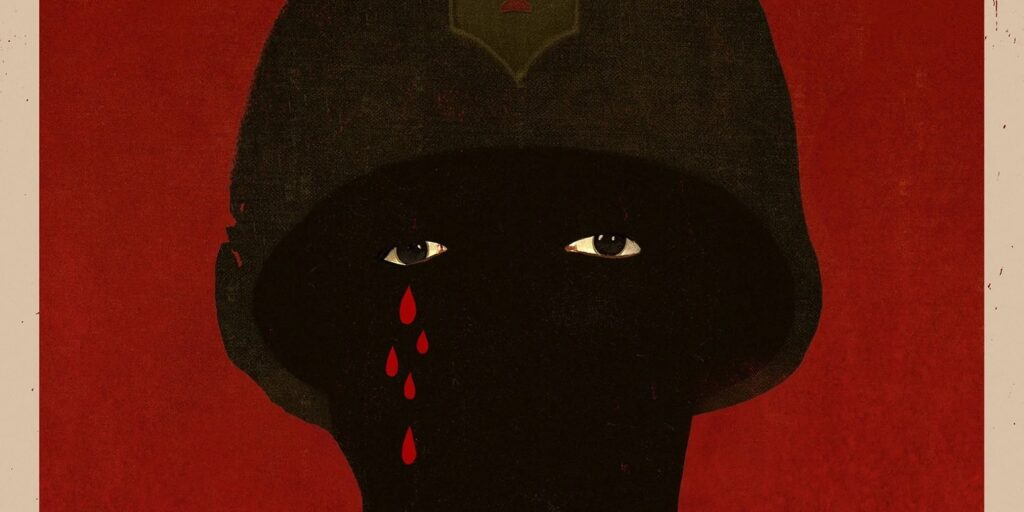

When Spike Lee showed his new film Da 5 Bloods to a test screening of veterans, one Black Vietnam War veteran asked “Spike, what the fuck took you so long?”.

The Vietnam War as a film sub-genre is a dense and complex minefield of political and social commentary, and some classics have inevitably become part of the historiography of the war. But looking back through the records, there’s no doubt that Da 5 Bloods feels long overdue, in that no other Vietnam War film has dedicated its narrative so solely to the experience of Black soldiers.

Spike Lee’s new joint about four Black veterans’ return to Vietnam takes on a largely unexplored element of the Vietnam War, forcing viewers to recognise the struggles Black soldiers faced by bringing these issues front-and-centre in a mainstream film. So it’s worth asking, what does Spike Lee bring that is new to the genre?

Da 5 Bloods may take viewers by surprise in that it is far from a conventional Vietnam War film. In fact, the only images of war you see are through flashbacks of battle and the squad’s fond memories of ‘Stormin’ Norman’ (Chadwick Boseman), who mentored, led and educated the group about the Civil Rights movement. Instead it focuses on the veterans’ present day return to Vietnam in search of the gold they had left buried there during the war. Lee’s story is not trying to be a statement about the realities of war. Rather, the film is both a treasure hunt and an adventure heist movie, and the elements which aren’t exclusively about the war provide some of its best moments.

It also shows Vietnam in a new light as the men dance in a club called Apocalypse Now, borrowing its name and iconography from Francis Ford Coppola’s classic, a choice Spike Lee described as paying homage to the film which had included two African-American characters, played by Albert Hall and a 14-year-old Laurence Fishburne.

The men walk through a modern, bright and vibrant Ho Chi Minh city, remarking on the western food options, enjoying the sights and taking in everything the new Vietnam has to offer. Lee does a fantastic job in showing the country in a new light, reminding the world of Vietnam’s status as a tourist haven and not a war-torn, economically underdeveloped country.

He also spoke of his desire for the film to redress the problematic depictions of both Black soldiers and Vietnamese characters, making sure to cast only Vietnamese actors, despite shooting much of the film in Thailand.

The film also features unexpected moments of insight into the Vietnamese experience of the war, such as allowing the audience to eavesdrop on one Viet Cong soldier talking about a poem his wife wrote him. Small moments of detail like this do not go unnoticed and through just one line of dialogue, Lee gives more personality to Viet Cong soldiers than a whole collection of older films do put together.

Other films do allow for moments of reflection on the human lives on the other side of the conflict, including the moment in Full Metal Jacket where Private Joker mercy kills a sniper who shot his comrade. But moments like this are more mechanisms for debate about vengeance, peace and morality than they are about the people themselves.

Whereas in contrast, Lee brings an element of realism to moments in Da 5 Bloods which is not motivated by superficial intentions to spark debate. However, Da 5 Bloods still falls slightly short of fully humanising the ‘other’ — the modern day ‘baddies’ out to get their hands on the gold are, on the whole, a faceless group who hold the same bland quality assigned to enemy soldiers in past Vietnam War films.

Statements on morality are another significant genre trait in Vietnam War films, where it has become commonplace for writers and directors to force the audience to go face-to-face with the atrocities and moral stalemates of war. Born On The Fourth of July shows the journey of a soldier who grew up as an all American patriot and then joins the anti-war movement. Apocalypse Now showcases the savagery and double standards littered throughout war. Platoon features a disturbing scene of atrocity, as well as two characters who represent opposite philosophies of war.

Da 5 Bloods steps away from this genre trait, focusing less on the moral question of the war itself and more on the morality of sending Black soldiers away to fight in Vietnam, when they were still fighting a battle of their own at home. Lee’s decision to refocus the genre to this facet of the conflict is a welcome spin on a much-explored genre, centring a narrative that was, until now, considered peripheral to the genre.

Da 5 Bloods does however follow in the footsteps of previous films by allowing time to explore individual trauma as a result of the war. Paul (Delroy Lindo) is particularly vocal about his struggles, as he unravels and faces his own demons and PTSD. The style and narrative structure of the film doesn’t allow for a deep dive into the long-lasting and everyday struggles of PTSD in the way that The Deer Hunter does, but it does well allowing for a condensed glimpse at war’s psychological impact in what is a mostly action-driven film.

Da 5 Bloods is sparking up so much debate undoubtedly because of the film’s racial focus. It has come onto our screens at an uncannily relevant time where the Black Lives Matter movement is at its most mobilised, and where the world is starving for more Black people-driven stories to redress the balance. And while some films such as Platoon and Apocalypse Now do address the racial disparity between Black and white soldiers, no mainstream film has tackled this divide like Da 5 Bloods does.

The film opens and closes on scenes of Martin Luther King, Malcolm X and Muhammed Ali, which immediately sets the film up as a piece of historical commentary as well as an action film. However, the reality of the Black experience in Vietnam is far more disturbing than what Lee sheds light on: disproportionate numbers of Black soldiers being made to fight and die on the front lines; soldiers who refused to carry wounded Black comrades; Ku Klux Klan rallies and cross burnings at US military bases.

What Spike Lee has done is set a precedent for a louder conversation to be had about the experience of Black soldiers in Vietnam, one which has thus far been ignored. And looking back at the Vietnam War movie genre, paired with the wealth of untold stories about Black soldiers’ experiences in Vietnam, it does beg the question… what did take so long?