Berwick-upon-Tweed, a small town almost slap bang on the border between Scotland and England, is the home of the UK’s Festival for New Cinema & Artists’ Moving Image. The festival ran for four days from the 19th September until the 22nd, featuring a wide range of films from new releases to revered classics and painstakingly restored cinema artifacts.

Now in its fifteenth year, the Berwick Film and Media Arts Festival (BFMAF) kicked off its programme with the UK premiere of Carlos Casas’ Cemetery (2019), selected as the official opening film. Cemetery offers a potent cocktail of mysticism, beauty and destruction, a mixture that categorises many of the films in the 2019 programme. Other films from the first day include Holy Days (2019), director Narimane Mari presenting the UK premiere of her dazzling and striking ballad, and the more children-orientated A Town Called Panic (2009). The programme also includes the annual Berwick New Cinema Competition, celebrating the best up-and-coming filmmaking talent and featuring a number of world premieres.

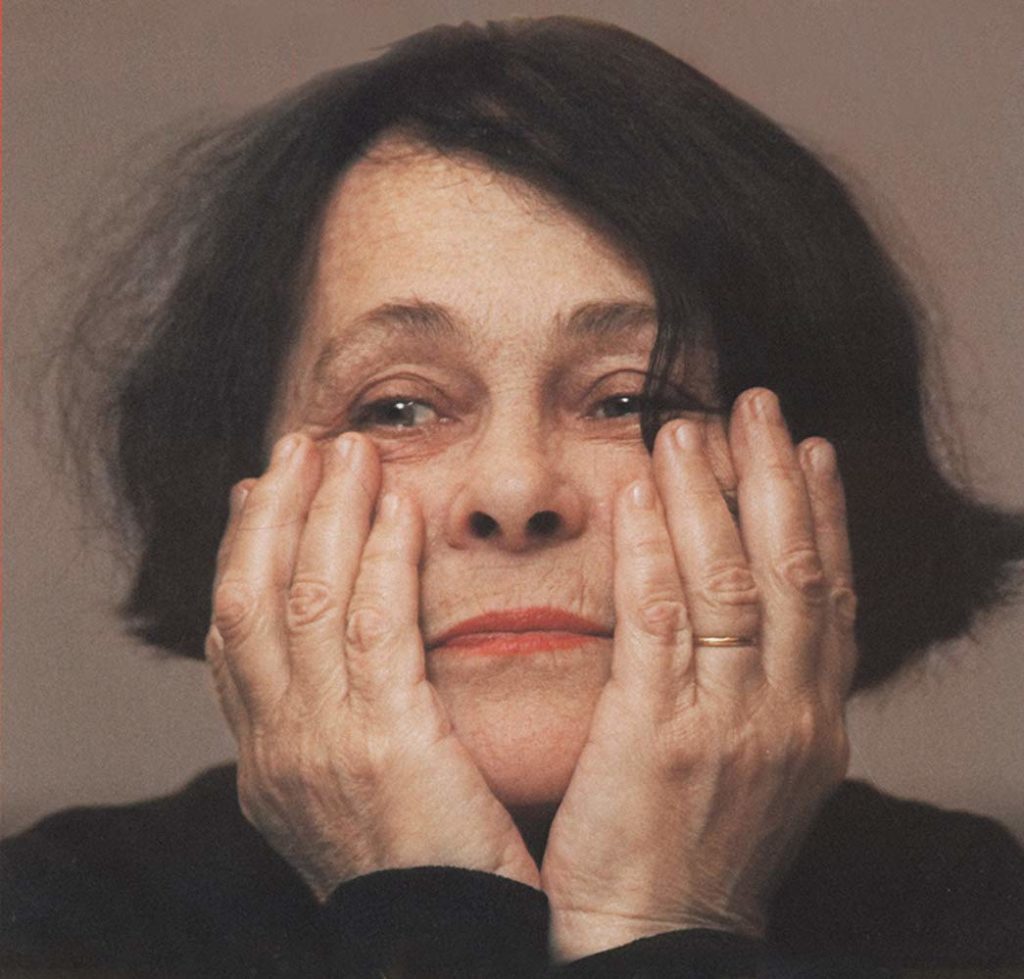

BFMAF’s Filmmaker in Focus this year is Kira Muratova; a titan of Russian-language cinema responsible for 22 unique works between 1961 and 2012. Having sadly passed away in June last year, aged 83, her work is being curated and celebrated in her honour. Muratova is best known for The Asthenic Syndrome (1989), winner of the Silver Bear at the 1990 Berlinale and screened on the festival’s penultimate day. A film effectively split in two, it captures the dying days of the USSR and two individuals’ melancholy in the face of hopelessness. It is often bleak, with some startling imagery and tableus that occasionally lean towards the absurd. It is a long two and a half hours, but if you are prepared to throw yourself into it, it becomes clear why The Asthenic Syndrome remains such a celebrated piece of art.

The first film of Muratova’s to play at the festival however is Brief Encounters (1967), her first solo feature film and made long before she became the subject of widespread international acclaim. An almost dreamlike love triangle story with melancholy and conflict also marks Muratova’s only major acting role, as well as announcing her as a talented cinematic auteur. The Long Farewell (1971), another Muratova film on the programme, is an affecting story of motherhood, womanhood and emotional attachment in the face of isolation. Also included this year is a double bill of two Muratova shorts, Getting to Know the Big Wide World (1978) and Letter to America (1999). Meanwhile, Passions (1994) marks a moment in Muratova’s filmmaking career where the form and presentation became more important than the story. Compared to the films she had made before the USSR collapsed, Passions is a more colourful, almost self-indulgent film that presents life with bright vividness and charm, rather than through harsh social realism. This is followed on the festival’s final day by Eternal Homecoming (2012), Muratova’s last film and one that features several big stars of Russian cinema such as Alla Demidova. Eternal Homecoming explores the possibility of transitions and blurring boundaries between the past and the present, a fitting end to a celebration of a director whose work will be felt for years to come.

The first feature film of the Friday is Moral (1982), a powerful and occasionally troubling drama covering queer families in the context of Filipino martial law. Receiving its UK premiere after almost forty years, it remains a standout piece of LGBT+, female-directed international cinema. This is followed by a documentary from the festival’s Artist in Profile, Marwa Arsanios. She presented the UK premiere of Who is Afraid of Ideology? (2019), a documentary of two halves looking at women’s movements and exploring topics such as ecology, war, feminism and economic hardship. Showing later on is Folk Legends, a curated short film collection of adapted folklore tales and legends that formed, or continue to form, part of each director’s cultural identity.

Later that day comes a screening of Broken Clocks, a collection of short films by Julia Feyrer originally shown as individually exhibited pieces. Later on that evening came two of the most intriguing UK premieres of the festival, the first being I Was at Home, But (2019) by Angela Schanelec. Characterised by sensitive camera placement, a beautiful aesthetic and family drama, the film went down at storm at the Berlin Film Festival earlier this year, Schanelec being awarded the Best Director prize for her efforts.

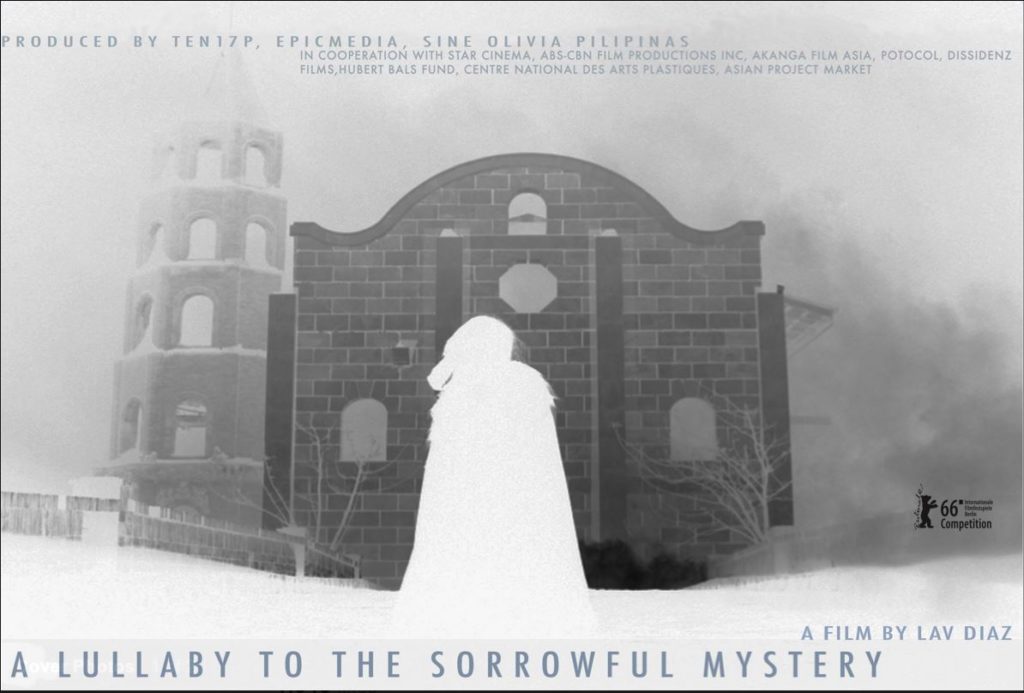

The final UK premiere of the night is of A Lullaby to the Sorrowful Mystery (2016), Lav Diaz’s enchanted and ambitious chronicle set during the Spanish thwarting of Filipino independence. At over eight hours long, it is a daunting but magical experience. Such a running time is to be expected however, since Diaz is a master of slow cinema. Another film of his receiving its UK premiere at BFMAF, The Halt (2019), is by comparison a breeze at a mere four hours and 43 minutes. A dystopian delve into surveillance and state politics, Diaz’s feature weighs in on the current political climate in The Philippines and is as immersive an experience as they come. Also rounding off the night is a double-bill screening of Un rêve plus long que la nuit (1976) and Hatsukoi (1989). The former is a psychoanalytic, psychedelic dive into the sexual female psyche, told with some sensational colour and sexualised absurdism. The latter is a short, gothic drama with no dialogue that laments a love that never materialises.

The first film of the Saturday afternoon is The Labour of Image Making, another project from Marwa Arsanios that brings together a collection of her short films, both old and new. Later that afternoon comes a screening of a carefully restored film directed by the late Lebanese filmmaker Christian Ghazi, A Hundred Faces for a Single Day (1971). Most of Ghazi’s works are believed lost or destroyed, making a public screening of any of his films a very rare occurrence. An experimental, pioneering avant-garde masterpiece, the film is a fascinating critique of class difference in the context of civil war and socio-economic hardship. Another filmmaker whose works deserve curation and restoration is Lionel Soukaz, a figurehead of queer cinema in Europe who produced a number of incendiary films, often challenging normative behaviour in romantic or sexual relationships. Militant Desire is a double bill screening of two Soukaz shorts, Royal Opera (1979) and Ixe (1980). The latter is one of the most explicit, electrifying and hypnotic short films you are ever likely to see, Soukaz transgressing all limitations with a trippy and endless rabbit hole of a movie. Rounding off the Saturday is Aleksey Fedorchenko’s fascinating and wonderful anthology film, Celestial Wives of the Meadow Mari (2012). Made up of 23 short stories, the film is at once tender, provocative and often quite funny – not to mention a genuine attempt to realise the lived reality of a minority ethnic group, complete with all of its fantastical yet taken for granted elements.

The final day begins with a screening of a unique result of the Czechoslovak New Wave, When the Cat Comes (1963). A stylish and transgressive comedy from Vojtěch Jasný that won the Cannes Special Jury Prize, the secret behind its success is largely down to Jasný’s collaboration with screenwriter Jirí Brdecka and main actor Jan Werich. In the afternoon, the Fairytale Shorts collection features four short films all themed around myth and storytelling; the Jethro Tull-produced Story of the Hare Who Lost His Spectacles (1973), Zlatko Bourek’s The Cat (1971), Anna Biller’s Fairy Ballet (1998) and the UK premiere of Cristóbal Léon & Cristina Sitja’s Strange Creatures (2019). Later in the afternoon, the curated three-film collection Windrush Legacies and Experimental Forms was shown. This brought together Zinzi Minott’s Fi Dem (2018) and Fi Dem II (2019) alongside Martina Attile’s Dreaming Rivers (1988), leading into discussions of the lineages and history behind Black experimental cinema in the UK. One of the final films of the festival – and one of the most well received – is Djibril Diop Mambéty’s The Little Girl Who Sold the Sun (1998), receiving its UK premiere after 20 years. An uplifting, hopeful and stunningly shot story, it proved the perfect note for many festival goers to bring their time in Berwick to a close.

The closing film of the festival this year was the Uk premiere of Juan Rodrigañez’s sharply written drama Rights of Man (2018). It is a film that manages to capture the spirit of cinema’s most classical auteurs while feeling very much like a contemporary, grounded piece of modern filmmaking. It is in many ways the perfect send off for the BFMAF, a unique festival that takes pride in celebrating the most exciting artistic talent in cinema while relishing the opportunity to restore and display important relics. The festival feels like it goes on far longer than four short days, and some of what you see is so searing that it will stay with you until you’re ready to do it all again the following year.