Early reactions following limited previews of Godzilla: King of the Monsters are positive. Something that emerges from these encouraging early statements is how close the new film has remained to its source material, while giving it a much-needed kick into action. The third film in Legendary’s MonsterVerse already looks like one that celebrates the long history of creature features and kaiju movies whilst also leaving its own mark on one of cinema’s weirdest histories.

Arguably, the first entry in this history is King Kong (1933), still renowned today for how it pushed the boundaries of special effects and scream factor. Its unmistakable racial commentary has guaranteed its enduring relevance, on top of being the movie phenomenon of the day; the Avengers: Endgame of 1933, if you will. What followed in later years was a whole slew of sequels and comparatives, such as the hastily assembled sequel Song of Kong (1933) and Mighty Joe Young (1949). Both King Kong and Joe Young got remakes later down the line (Kong’s original story has been retold twice – in 1976, then in 2005). Such films helped to ensure the popularity of the colossal ape movie, represented today by the likes of Kong: Skull Island (2017) and the testosterone-fuelled safari that is Rampage (2018). And that’s without throwing in the countless low budget, B-movie flicks that owe their existence to these early films.

2017’s Skull Island is of course another MonsterVerse film, one that reimagined the great ape’s story to give it a different importance. However, King of the Monsters has a more obvious debt to post-war Hollywood and the nuclear-monster mania of the 1950s. As the Cold War hung over the American population like a radioactive fog, movies such as Them! (1954) and Tarantula! (1955) became increasingly common. They tapped into the fears of nuclear warfare and technology or, more broadly, of science dabbling where science shouldn’t. In Them!, ants have been mutated to an enormous size by nuclear tests. The creatures embodied in monstrous form the fear and paranoia induced by nightmares of Armageddon. An even earlier example is The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), in which the dinosaur-esque monster is awoken by nuclear testing and proceeds to the destruction of cities. Yet its legacy has been somewhat overshadowed by a film released the following year that has a similar premise, yet hit a nerve with its audience that the American creature features dared not touch.

Godzilla (1954) is also about a reptilian beast who emerges from the water following nuclear testing, and who also proceeds to level cities. Except, with the film having been made in Japan by Toho Studios, the monster took on a completely new meaning. Japan was only just starting to demand recognition and remembrance for the victims of the nuclear bomb drops on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, two acts of brutality that brought World War Two to a sudden end. American forces occupied Japan for seven years following the war, during which time both they and the Japanese buried the memories of the nuclear horror. However, following the Lucky Dragon incident, demands for remembrance grew, and it was amidst this public maelstrom that Godzilla surfaced.

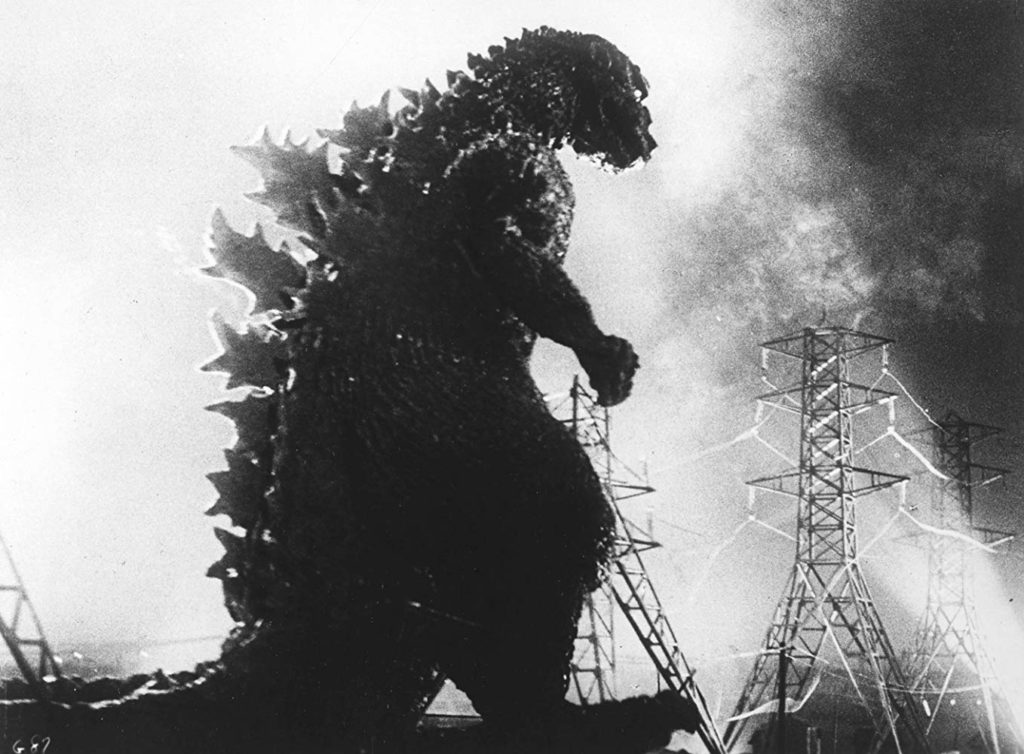

The original Godzilla might not have pushed the boundaries of special effects like American movies were doing. Visually, it just about matches up with King Kong, which came some 21 years before it, and has the unavoidable ‘guy in a rubber suit’ vibe about it. Yet the importance of Godzilla cannot be overstated. While American monster flicks were meant to be fun and a bit ludicrous, Godzilla is a sobering trudge through national mourning, pain and guilt. This unstoppable force, a powerful allegory for nuclear weapons, brought with it the inevitability of fate and, in some interpretations, punishment. It takes a scientist’s invention of a dangerous weapon to vanquish the monster; the Japanese scientist then sacrifices himself so as to ensure his own destructive tools can never be used again. It bears immediate comparisons to Japan’s kamikaze pilots during the war, except this is not fuelled by national honour, but by fear and shame. Endless dissections of film and beast point to Godzilla as not only a powerful anti-nuclear statement, but as a figure plaguing the Japanese national consciousness for the country’s own wartime atrocities, and the subsequent devastation suffered by its citizens.

The film was a box-office success, and gave birth to the longest-running franchise in film history. It struck an emotional chord with Japanese audiences that guaranteed the monster’s place in history, and is widely regarded as the first of the kaiju movies (kaiju being Japanese for ‘strange beast’). An incredible boom in production followed on both sides of the Pacific, introducing new monsters into the fray; while the Japanese film industry was buoyed by the success of Godzilla and all of its sequels and spin-offs, in America new monster flicks arrived thick and fast, fuelled by the creative genius of Ray Harryhausen. Harryhausen oversaw the design of creatures across a myriad of American blockbusters, such as The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) and Jason and the Argonauts (1963). On occasion the two came together as well, seen in the cult classic King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962), which is getting a reboot due for release next year. The creature feature was in full swing.

It did not last. As the threat of nuclear war slowly dissipated, the whole basis for investment in the creatures crumbled. New relevance was needed – the quest to keep giant monsters relevant is a struggle that underpins almost the entire history of creature features. Environmental concerns replaced nuclear fears from the mid-1960s onwards, best seen by Frogs (1972) – starring suspiciously few frogs – and similar films such as Piranha (1978) that dealt with the nasty ecological consequences of human activity. Jaws (1975) cannot go unmentioned, although Steven Spielberg’s groundbreaking summer hit arguably helped to make the figure of the kaiju increasingly less mainstream. Gone were giant beasts towering over cities, and in came either monstrous animals like sharks or more human monsters like Michael Myers or Freddy Krueger. In any case, they were much smaller. Improved production effects may have played a part in this too – make-up and costume advances proved far more convincing than a guy in a dino suit, and the horror surge of the 1980s would become far more popular. Even Toho, who had been grinding out Godzilla films for years by this point, only released two in the whole of that decade – the same number they released in 2018 alone.

However, Spielberg also helped to reverse the trend with the Jurassic Park movies, which helped to rekindle the lost love for creature features. Sensationally popular and still holding up today, perhaps the quintessential ‘90s blockbusters returned to the themes of the old B-movies and kaiju flicks, by placing science at the core. The conversation between Richard Attenborough and Jeff Goldblum’s characters in the first Jurassic Park (1993) blatantly spits out the same dilemmas that underpinned Godzilla, Them! and all comparable creature features – “your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, that they didn’t stop to think if they should.” Cue a revitalised monster genre, with Toho releasing more Godzilla films in the 1990s as monsters charged for the new millennium with newfound confidence. The first of the more recent American reinventions of Godzilla also came in this decade, very much riding off the coattails of Jurassic Park’s success. It tried its best to stay true to the original, but has emerged as the kind of forgotten hit that Channel 5 now screens to fill up airtime.

In the wake of the 9/11 terror attacks, creature features and cinema in general was injected with a newfound knack for searing politics. A fascinating example is the South Korean film The Host (2006), which can be read as a metaphor for American presence during the occupation of the country between 1945 and 1948. The most memorable example, however, has to be Matt Reeves’ Cloverfield (2008). Cloverfield effectively reinvented the kaiju for the digital age, the mobile phone camerawork capturing a terrified frenzy and confusion that is all too comparable to what we see on the news today in the aftermath of disaster. It captures the fear of terrorism that lurks just below the surface in American society, with unmistakable references to September 11th. As if to rub in the point, the film poster shows the Statue of Liberty – a symbol of American power, democracy and freedom – with its head ripped off. This is no fantasy-fuelled science fiction swagger like the B-movies of the 1950s. In many ways, Cloverfield is more like the original Godzilla; an unforgiving, relentless monstrosity that tears through the fabric of the national imagination.

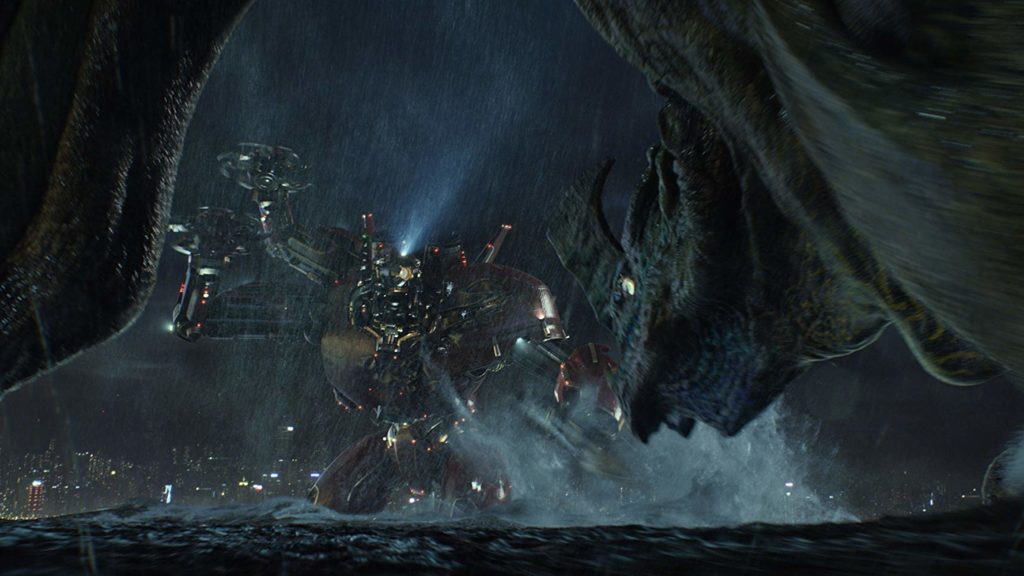

What definitively heralded the return of the kaiju to the mainstream however, was Pacific Rim (2013). What could have been a forgettable and peculiar fantasy was handled with class and style by director Guillermo del Toro. Even though the kaijus are from space, they come to earth via a portal underneath the sea, a fantastic return to the old way of introducing monsters to the surface world. Giant robots fighting kaijus from space sounds ridiculous, yet somehow Pacific Rim is rousing and enjoyable. Perhaps it’s due to the childlike wonder and curiosity towards big machines and big monsters that it rouses, relishing in finer details that most creature features tend to miss. Alternatively, it could be the optimistic tone of cooperation and unity that underpins the story – something to treasure in an era that seems more ideologically fractured than ever. The pessimism of the 2000s gave way to adrenaline-fuelled escapism, and it worked. The film under-performed in America, but was hugely popular internationally, especially in China. By modern blockbuster standards, around $400 million at the box office might seem a bit puny for a film that cost $200 million to make, but the influence of Pacific Rim reached out beyond singular film markets to have a global reach.

Then in 2014, Legendary launched the MonsterVerse with their reboot of Godzilla. Released in collaboration with Toho, Legendary needed a new franchise to take them forward, following the success of the Dark Knight Trilogy. Godzilla was the answer, and the studio consistently demonstrate that they care about getting it right. For both this and King of the Monsters, the studio brought in Yoshimitsu Banno as an executive producer, credited posthumously for the latter following his death in 2017. He is best remembered as the director of one of Toho’s more pulpy hits, Godzilla vs. Hedorah (1971). Toho studios heavily contributed to the design of Godzilla, which is evident when comparing the new version of the monster to the original: it seems more like an update than a reinvention. Motion capture was used to capture Godzilla’s movements – which when you think about it, is just the modern equivalent of the rubber suit.

You can of course find faults with Godzilla, but it won over fans with its surprisingly restrained approach, its odes to Spielberg and for honouring the history of the world’s most famous kaiju. Important to this is how Godzilla has been reimagined yet again. Rather than a metaphor for nuclear weapons, Godzilla here represents an uncontrollable, natural force. He normally resides close to the core of the earth where radiation is stronger, a representation of how fundamental he is to the planet’s health. He has, as one character puts it, the power to restore balance. He no longer represents the nuclear threat, but instead attempts to control it, trading blows with the other monsters who feed off radiation like he does. The power of nature is a theme repeated throughout, with references to Hurricane Katrina and the Fukushima Daiichi disaster of 2011. The latter is powerfully invoked near the film’s beginning when a nuclear plant collapses. Godzilla is a warning of the consequences of nuclear power in general, be it for bombs or electricity. Unlike in the original, here the nuclear threat is not carried over from America to Japan, but from Japan to America. It is the narrative arc of “reverse colonisation,” as identified by Stephen Arata. Guilt for past atrocities (nuclear bombing, as referenced in a poignant moment in the film) emerges as a fear of attack and disaster coming from the abode of the ‘other,’ seen as a risk to normal ways of life. This threat had manifested in the real world barely three years prior with Fukushima, which triggered a revival of nuclear paranoia around the world. Godzilla took the kaiju and gave it new meaning, twisting its appeal in order to spectacularise a meaningful geopolitical point.

Promotional material for King of the Monsters shows this process of change continuing, while again honouring the zany history of the genre. Very obvious is that the film will have some kind of commentary on climate change, and the ‘titans’ will be crucial to saving the planet. Naturally, it’s not quite so simple. Unlike with its predecessor, which plucked new monsters out of thin air, King of the Monsters dives deep into Godzilla’s history to revive kaijus once thought confined to alternative fandom. Mothra, Rodan and King Ghidorah – all old foes of Godzilla – have been brought back to life. The tantalising premise has already delivered some powerful shots. In the wake of the Extinction Rebellion protests up and down the UK, and the re-energised awareness of climate change more broadly, the sight of an oil field ripped up by an emerging monster has real potency. The climate and the health of our planet is now front and centre for the MonsterVerse, and the kaiju movie can hammer home the most important issue of the 21st century like few other genres can.

But it is not just in these serious, politicised ways that Legendary continue to pay homage to these creatures. What characterises the history of kaiju flicks more than anything is creative teams letting their imagination run wild. Can Godzilla breathe blue fire? Sure he can. Why does King Ghidorah have the power to shoot lightning from his wings? He just does. Legendary could have gotten rid of such over-the-top details, but have opted to keep them. They respect the madcap efforts of those responsible for bringing these beasts to life in the first place, and refuse to erase that history. The end result looks like a film that will have serious points to make, but does not forget what it is – a colosseum for gigantic monsters to do battle.

In Pacific Rim, the jaeger robots need two pilots neurologically linked in order to control the machine and fight a kaiju. Legendary’s reimagining of Godzilla depends on a similar kind of balance and unity. On one hand, it respects and pays homage to the long tradition of kaiju movies, in all their strangeness, ensuring that the monsters stay relevant and represent some kind of lurking terror. On the other, they make sure that the monsters are as entertaining as they are important. This blend of historical influence and contemporary relevance is what makes the MonsterVerse one of the most fascinating franchises of modern Hollywood, and it is just as well. With Disney’s acquisition of Fox and their increasing monopolisation of movies, the MonsterVerse is now one of the biggest series that is not resident in the house of mouse. For anyone invested in a film industry that is creatively diverse, it is in their best interests that Godzilla roars again.

Godzilla: King of Monsters releases on May 29th, distributed by Warner Bros.