Vox Lux is Brady Corbet’s sophomore directorial feature, an outrageously fun yet deeply sad film about a pop diva whose fame is forged in the horror of a 1999 school shooting, a thinly veiled reference to Columbine. It is a heart-breaking, yet visually stunning opening act that sets the tone for what is to come.

The tragedy leaves a single survivor, 14-year-old Celeste Montgomery (the ever-talented Raffey Cassidy), wounded to her back and neck and profoundly traumatised by what she witnessed. At a vigil for her classmates, Celeste is asked to speak but is unable to express herself, and instead offers a song for her fallen friends that will catapult her to stardom.

Narrated by Willem Dafoe in a cynical and ironic voiceover, Vox Lux is split into two acts. The first is titled ‘Genesis’ and follows a young Celeste as the navigates her new-found fame and begins to build a pop career under the guidance of her nameless manager (Jude Law). The second act, ‘Regenesis’, jumps ahead to 2017 where Celeste (now played by Natalie Portman) prepares for her homecoming tour after a series of scandals damaged her image.

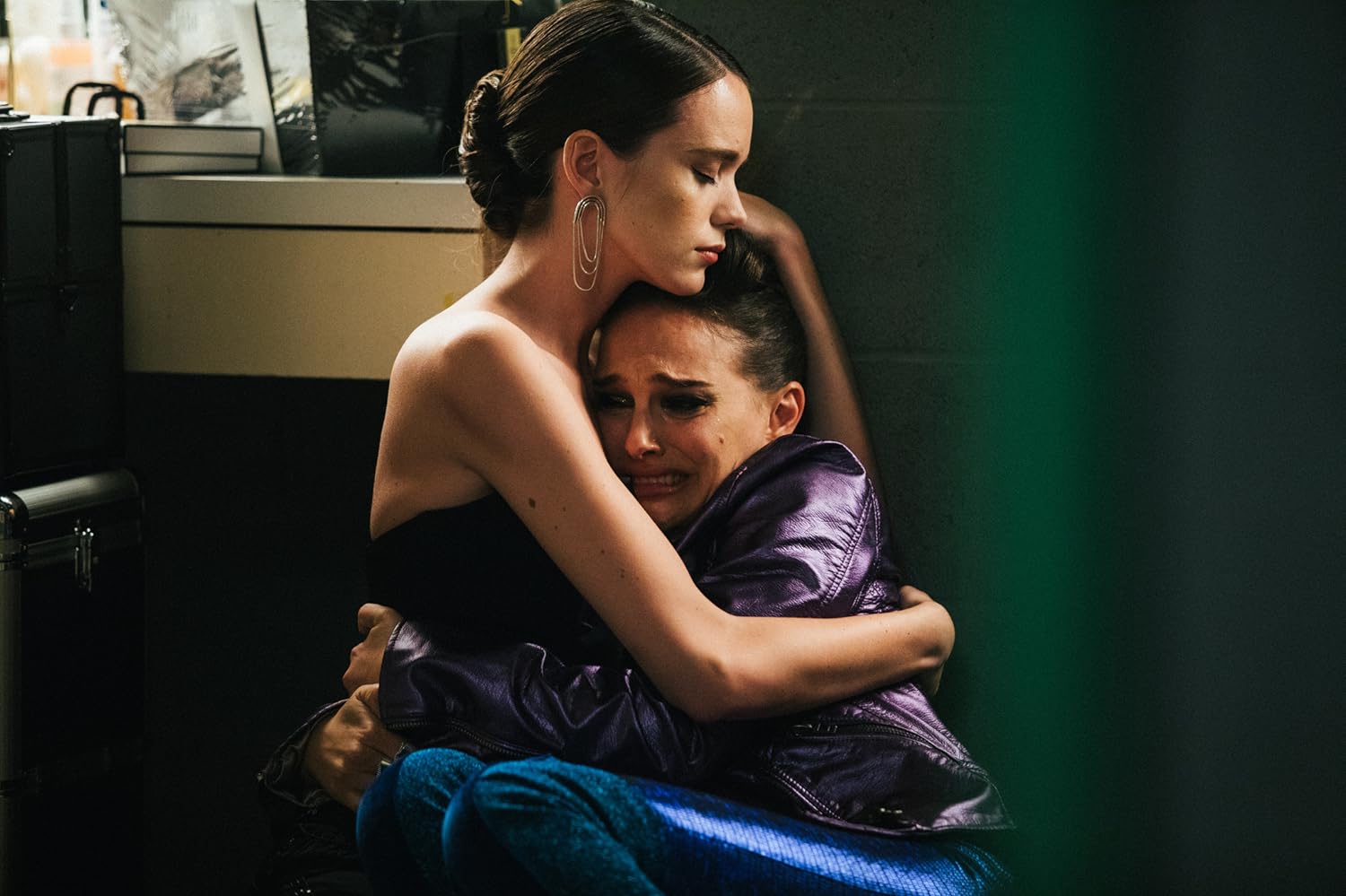

Through this progression, Corbet explores the psychological effects of overnight fame, the loss of innocence, the sped-up nature of time, the loneliness and emptiness it leaves behind. Natalie Portman is a powerhouse, throwing herself head-first into the role as a jaded diva, in what is undoubtedly her most addictive performance to date.

‘Regenesis’ is fascinated by the messiness of public life, by the way that Celeste’s friends and family are trapped in her life and suffering from the star’s unpredictability and overwhelming intensity. While both her public and personal lives have descended into chaos, things are only exacerbated when terrorists in Croatia use part of her iconography – a bejewelled mask – to carry out a mass shooting.

Vox Lux does not follow typical movie grammar, nor does it insist on following any real plot. In spite of this, or perhaps because of it, the film does not once, in its 115-minute runtime, loosen its grasp on the audience. It’s disorientating, ambitious, beautiful, and existentially devastating.

These dualities are further underlined by the two distinct musical voices in the score: Scott Walker’s orchestra gives the film grandeur, transforming the landscape into a mysterious, at times threatening world. On the other hand are Sia’s songs, performed by Portman, pop anthems with catchy choruses and feel-good beats. The contrast between both voices further emphasises the instability and conflict which reigns over the story.

Despite the film’s conversation on violence, art, and the commodification of stars, Corbet does not turn Vox Lux into a sermon on the dangers of fame. It simply observes, and leaves the viewer with a hollow feeling so at odds with the incredible fun they have just had. It is those very contradictions that make for a stunning and affective viewing.

Vox Lux is out in cinemas, distributed by Curzon Artificial Eye.